Ulysses chapter I Telemachus interpretation by Prof.Stuart Gilbert

He covers the same items with the same binders in the framework we are using, With the exception of Technic wich he uses only Narrative, Young and we use Linati indicating Dialogue between 3, 4, people, narrative, soliloquy.

notes:

1 - There is a copyright

issue here that has to be solved as already mentioned in the Introduction. As

it is it is, is ok under the 10% free quotation rule.

2 -This edition relates the text to the pages of the initial Editions by Sylvia

Beach, Odyssey Press, 1932, that in the background is the 1961, which we used;

3- It should be created a repository

for the S Gilbert, that will result in a translation of his book, if

this project ends up as planned, this will occur for the selected languages.

TELEMACHUS

| SCENE | The Tower |

| HOUR | 8 a.m |

| ART | Theology |

| SYMBOL | Heir |

| TECHNIC | Narrative (young) |

Glueing, cohesive, bonding, focus, unifying elements above are highlighted in the text.

8 a.m. is implicit and deductible

Theology is found only once on a foot note, and refers to mythologic theology, which is implicit

Narrative (young) is implicit

97

The first three episodes

of Ulysses (corresponding to the Telemachia of the Odyssey) serve as

a bridge-work between the Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the

record of Mr Bloom's adventures on the memorable date of June 6th, I904. The

closing lines of the Portrait (extracts from the diary of Stephen Dedalus)

not only throw considerable light on Stephen's character but also contain premonitions

of certain of the motifs which (as I have suggested in my introduction)

are essential to the understanding of Ulysses.

"April 26. Mother is putting my new secondhand clothes in order.

She prays now, she says, that I may learn in my own life and away from home

and friends what the heart is and what it feels. Amen. So be it. Welcome, O

life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and

to forge in the smithy of my soul) the uncreated conscience of my race.

"April 27. Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good

stead."

Thus Stephen invokes the example and patronage of the inventor of the labyrinth, first artificer to adapt the reality

98

of experience to the rite

of art,(1) first flying man, teacher of "transcendental mysteries"

and of astrology,(2) in the huge task he has set before him.

A little over a year has passed since Stephen recorded these entries in his

diary. During this period he has encountered something of the reality of experience-a

taste of Parisian life, the shock of his mother's death and the hard constraint

of earning his living by distasteful work (as teacher in a small school). But

most "realistic" of all, perhaps, is his daily contact with "Buck"

(Malachi) Mulligan, a cynical medical student, deliberately boorish in manners,

with an immense repertoire of lewd jests and blasphemous doggerel. Stephen is

living with Mulligan in a disused Martello tower,

overlooking Dublin Bay; Stephen pays the rent but Mulligan insists on keeping

the key.

The opening scene is enacted on the platform of this tower.

Mulligan comes forth from the stairhead "bearing a bowl of lather on which

a mirror and razor Iay crossed".

Hoiding up the bowl he intones:

Introibo ad altare Dei.

(Ulysses thus opens on a ritual note, the chant of an introit on the summit

of a round tower. and the elevation of a bowl bearing

the holy signature.)

Presently Stephen joins Mulligan who, thrusting a hand into Stephen's upper

pocket, says:

"'Lend us a loan of your snotrag (3) to wipe my razor.'

"Stephen suffered him to pull out and hold up on show by its comer a dirty

crumpled handkerchief. Buck Mulligan

(1) "The period represented

by the name of Daedalus was that in which such forms. [the conventional forms

of art] were first broken through, and the attempt was made to give a natural

and lifelike impression to statues, accompanied, as such a development in any

branch of art always is, by a great improvement is the mechanics of art."

Smith's Dictionary of Biography and Mythology.

(2)According to Lucian.

(3)The Oxford Dictionary proscribes the word "snot" and its adjective

as "not as decent use"; but the latter, anyhow, has be canonized by

the pious George Herbert in jacula Prudentun: 'Better a snotty child than his

nose wiped off."

99

the razorblade neatly. Then, gazing over the handkerchief he said:

"The bard's s noserag. A new art colour for our Irish poets: snotgreen.

You can almost taste it, can't you?'"

In sudden Swinburnean, mood Mulligan hails the "great sweet mother".

"'Thalatta! Thalatta! She is our great sweet mother. Come and look.'

"Stephen stood up and went over to the parapet. Leaning on it he looked

down on the water and on the mailboat clearing the harbour mouth of Kingstown.

"Our mighty mother,' Buck Mulligan said."

Abruptly Mulligan swings round and reproaches Stephen for his conduct at his

mother's deathbed.

"You could have knelt down, damn it, Kinch,(1) when your dying mother asked

you. I'm hypoborean as much as you. But to think of your mother begging you

with her last breath to kneel down and pray for her. And you refused. There

is something sinister in you…. "

They continue talking and presently Mulligan grows aware that Stephen is nursing

a grievance against him.

"What is it?' Buck Mulligan asked impatiently. 'Cough it up. I'm quite

frank with you. What have you against me now?'

"They halted, looking towards the blunt cape of Bray Head that lay on the

water Iike the snout of a sleeping whale. Stephen freed his arm quietly.

"'Do you wish me to tell you?' he asked.

"You were making tea,' Stephen said, 'and I went across the landing to

get more hot water. Your mother and some visitor came out of the drawingroom.

She asked you who was in your room.'

"Yes?' Buck Mulligan said. 'What did I say? I forget.'

"'You said,' Stephen answered, 'O it's only Dedalus whose mother is

beastly dead.'

(1)"Kinch the knifeblade" is Mulligan's nickname for Stephen.

100

"A flush which made

him seem younger and more engaging rose to Buck Mulligan's cheek.

"'Did I say that?' he asked. 'Well? What harm is that?'

"He shook his constraint from him nervously. "'And what is death,'

he asked, 'your mother's or yours or my own? You saw only your mother die. I

see them pop off every day in the Mater and Richmond and cut up into tripes

in the dissecting room. It's a beastly thing and nothing else. It simply doesn't

matter. You wouldn't kneel down to pray for your mother on her deathbed when

she asked you. Why? Because you have the cursed Jesuit strain in you, only it's

injected the wrong way. To me it's all a mockery and beastly. . . . Absurd!

I suppose I did say it. I didn't mean to offend the memory of your mother.'

"He had spoken himself into boldness. Stephen, shielding the gaping wounds

which the words had left in his heart, said very coldly:

"'I am not thinking of the offence to my mother.'

"'Of what, then?' Buck Mulligan asked.

"'Of the offence to me,' Stephen answered.

"Buck Mulligan swung round on his heel.

"'O, an impossible person!' he exclaimed."

For breakfast in the livingroom of the tower they

are joined by Haines, a young Englishman who is lodging with them, a literary

tourist in quest of Celtic wit and twilight. Mulligan presides at the meal.

"'Bless us, O Lord, and these thy gifts. Where's the sugar? O, Jay, there's

no milk.'

"Buck Mulligan sat down in a sudden pet.

"'What sort of a kip is this?' he said. 'I told her to come after eight.'

While they are taking breakfast the old milkwoman arrives; Stephen "watched

her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers.

Old shrunken paps. She poured again a measureful and a tilly. Old and secret

she had entered from a morning world, maybe a messenger . . . Crouching by a

patient cow at daybreak in the Iush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled

fingers

101

quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle.

Silk of the kine and poor old woman, names given her in old times. A wandering

crone, lowly form of an immortal serving her conqueror and her

gay betrayer, their common cuckquean, a messenger from secret morning. To serve

or to upbraid, whether he could not tell: but scorned to beg her favour."

"Silk of the kine" and "poor old woman" are old names in

Ireland; in the milkwoman Stephen sees a personification of Ireland and in his

musings we discern his attitude the "dark Rosaleen" school of thinkers.

He refuses to

cringe to the narrow patriots who surround him and to exploit the sentimentalism

in favour with the Dublin literary group. Thus, watching Mulligan shave holding

up a cracked mirror ("I pinched it out of the skivvy's room"), Stephen

bitterly observed:

"It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked lookingglass (1) of a servant."

Haines, impressed by Stephen's epigram, asks if he may make a collection of

his sayings.

"'Would I make money by it?' Stephen asked.

"Haines laughed and, as he took his soft grey hat from the holdfast of

the hammock, said:

"'I don't know, I'm sure.'

"He strolled out to the doorway. Buck Mulligan bent across to Stephen and

said with coarse vigour:

"'You put your hoof in it now. What did you say that for?'

"'Well?' Stephen said. 'The problem is to get money. From whom? From the

milkwoman or from him. It's a toss up, I think."

(Stephen cynically speculates which country is the more exploitable.)

After breakfast they walk to the sea and Mulligan bathes. Haines sits on a rock,

srnoking

(1)An echo of Oscar Wilde. "I can quite understand your objection to art being treated as a mirror. You think it would reduce genius to the position of a cracked Iooking-glass." Intentions (1894), page 31.

102

"Stephen turned away.

"'I'm going, Mulligan,' he said.

"Give us that key, Kinch,' Buck Mulligan said, 'to keep my chemise fiat.'

"Stephen handed him the key. Buck Mulligan laid it across his heaped clothes.

"And twopence,' he said, 'for a pint. Throw it there.'

"Stephen threw two pennies on to the soft heap. Dressing, undressing. Buck

Mulligan erect, with joined hands before him, said solemnly:

"He who stealeth from the poor lendeth to the Lord. Thus spake Zarathustra.'

"His plump body plunged.

"We'll see you again,' Haines said, turning as Stephen walked up the path

and smiling at wild Irish.

"Horn of a bull, hoof of a horse, smile of a Saxon."

Stephen is the central figure in this episode (as in the two following: Nestor,

Proteus). Despite the encounters he has had with the reality of experience,

he remains the young man we knew in the Portrait of the Artist. That book was,

doubtless, autobiographical in the main, and, in this episode, too, a personal

note is discernible. But Stephen Dedalus represents only one side of the author

of Ulysses, the juvenile, self-assertive side, unmodified by maturer wisdom.

The balance is redressed by the essentially "prudent" personality

of Mr Bloom, who is, indeed, as several critics have pointed out, not merely

the protagonist of the book, but a more likable character than Stephen. The

somewhat irritating intransigence of the latter-his insistence on the servility

of Ireland, Irish art, all things Irish, and his fanatical refusal to kneel

at his mother's deathbed '-is a sign of immaturity, far removed from the tolerant

indifference (to all but aesthetic problems) of the author. Indeed, Stephen

Dedalus,

(1)Actually this incident Mr Stanislaus Joyce tells us, "has been overdramatized". "The order (to kneel and pray) was given in a peremptory manner by an uncle, and it was not obeyed; Joyce's mother by then was no longer conscious." (Recollections of James Joyce, by his Brother. The James Joyce Society.) It must be borne in mind that Ulysses, like the Portrait, is not a mere reportage but, supremely, a work of art, stylized as are Byzantine figures, or EI Greco's.

103

as we see him in the Portrait and these early episodes of Ulysses, could

hardly of himself have created a Leopold Bloom, that lively masterpiece of Rabelaisian

humour and rich earthiness. From what we learn of the hero of Ulysses, is easier

to believe that a Leopold Bloom, enlightened and refined by a copious, if eclectic,

course of philosophy, Iogic, rhetoric, metaphysics, and drawing upon the resources

of s own prodigious memory, might have been the creator Stephen Dedalus, his

"spiritual son".

We have not yet entered upon the Odyssey proper and the Homeric recalls in this

and the two following episodes less precise than those in later chapters which

deal with adventures of Mr Bloom. Some general correspondences, however, may

be noted between the presentation of Stephen's character and circumstances in

this episode and the Telemachia, or prelude of the Odyssey.

The first two Books of the Greek epic describe the plight of Telemachus in his

father's palace at Ithaca, where the Suitors of his mother Penelope are in possession,

wasting his substance, mocking his helplessness. "Telemachus," the

suitor Antinous says, "never may Cronion make the king in seagirt Ithaca,

which is of inheritance thy right." Thus, too, Buck Mulligan lords it in

the Martello tower; Stephen pays the rent but Mulligan

keeps the key. The "Buck" is far wealthier than Stephen, yet he makes

Stephen hand him "twopence for a pint", and demands that when Stephen

gets his pay from the school that morning he shall not only lend him "a

quid" but bear the expenses of a "glorious drunk to astonish the druidy

druids". In talking S Stephen he usually adopts the patronizing, bullying

tone of Antinous with Telemachus.

Stephen in the Portrait declares that he will use for his defence "the

only arms I allow myself to use, silence, exile and cunning". Those were

the only arms of Telemachus, defenceless among the overweening wooers of Penelope.(1)

(1)Not till Athene gave him heart did Telemachus quit his "moody brooding", the silence of despair. When, encouraged by the goddess, he told Penelope that he was at last going to speak "like a man", "in amaze she went back to her chamber". (Odyssey. I. 360.)

104

And, like Stephen, "Japhet

in search of a father" (as Mulligan calls him), Telemachus sets out from

Ithaca to Pylos in quest of his father, Odysseus, ten years absent from home.

Each personage of the Odyssey has his appointed epithet and, when he is about

to speak, the passage is generally introduced by a set formula. (Homer, unlike

modern writers, always uses the introductory "he said", "he asked",

"he replied", etc., when one of his characters speaks; in this practice

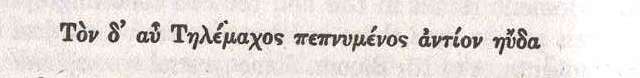

he is followed by Joyce.) The formula for Telemachus is:

Butcher and Lang translate:

"Then wise Telemachus answered him and said …" In this rendering

the literal meaning of irarvvc'voç is not sufficiently brought out. M.

Bérard's translation seems more exact: "Posément Télemaque

le regarda et dit . . ." This version also elicits the full meaning

of Homer's &vi-toy. Telemachus, like Hamlet, has a trying part to play.

He has acquired, perforce, a wisdom beyond his years and learnt to act and speak

posément, deliberately, to take thought before he speaks and to hide

his thoughts beneath a veil of ambiguity or reticence.

In a brilliant, but (as it seems to me) unjustified diatribe on the personality

of the author of Ulysses as depicted (or supposed to be depicted) in the character

of Stephen Dedalus, a distinguished polemist has ridiculed Stephen's habit (especially

noticeable in this episode) of answering people "quietly", and the

languid deliberation of his movements. But it is obvious that these mannerisms

are in keeping with his Hamlet-Telemachus rôle; they are the defences

of a character unable to take arms against a sea of troubles, yet determined

to preserve his personality in the face of scorn and enmity. Telemachus is one

who "fights from afar", au-dessus de la mêlée.

The old milkwoman, "witch on her toadstool", in whom Stephen saw a

personification of Ireland, reappears under the name of Old Gummy Granny in

the Circe episode.

105

"(Old Gummy Granny

in sugarloaf hat appears seated on a toadstool, the death flower of the potato

blight on her breast.)

"STEPHEN. Aha! I know you, grammer! Hamlet, revenge! The old sow that eats

her farrow!' (1)

"OLD GUMMY GRANNY (Rocking to and fro.) Ireland's sweetheart, the

king of Spain's daughter alanna. Strangers in my house, bad manners to them!

(She keens with banshee woe.) Ochone! Ochone! Silk of the kine! (She

wails.) You met with poor old Ireland and how does she stand?

"STEPHEN. How do I stand you? The hat trick! Where's the third person of

the Blessed Trinity? Soggarth Aroon? The reverend Carnon Crow." (2)

When a drunken British soldier is about to knock Stephen down, Gummy Granny thrusts a dagger towards Stephen's hand.

"OLD GUMMY GRANNY Remove him, acushla. At 8.35 a.m. you will be in heaven and Ireland will be free."

She is a recall of Mentor,

or rather of that other "messenger from the secret morning", Athene,

who in the likeness of Mentor in fashion and in voice drew nigh to Telemachus,

to serve and to upbraid, and hailed him in winged words, bidding him be neither

craven nor witless, if he has a drop of his father's blood and a portion of

his spirit.

The symbol of this episode is heir

(obviously appropriate to Telemachus) and in it the themes of maternal love

(perhaps, as Stephen says elsewhere, "the only true thing in life")

and of the mystery of paternity (3) are first introduced. Haines speaks of the

"Father and the Son idea. The Son striving to be atoned with the father",

and Stephen muses on certain heresies of the Church, concerning the doctrine

of consubstantiality.

(1) Ireland is the old

sow that eats her farrow." A Portrait of the Artist, page 238.

(2) Stephen has a trinity of masters, as he tells Haines: British, Irish and

the holy Roman catholic and apostolic church.

(3) See Chapter III, § 4 of my Introduction.

106

Like Antinous and the other

suitors, Mulligan and his ilk would despoil the son of his heritage or drive

him into exile.

"A voice,(1) sweettoned and sustained, called to him from the sea. Turning

the curve he waved his hand. It called again. A sleek brown head, a seal's,

far out on the water, round.

"Usurper."

Finally, the heir

is a link between the past and the generations of the future, as this episode

is between the Portrait and Mr Bloom's Odyssey which is to follow.

Another theme introduced here is Stephen's remorse for his (averred) refusal

to obey the last wish of his mother- Agenbite of Inwit.(2) The vision of his

mother's deathbed haunts Stephen's thoughts by day and his dreams by night.

"In a dream, silently, she had come to him, her wasted body within its

loose graveclothes giving off an odour of wax and rosewood, her breath bent

over him with mute secret words, a faint odour of wetted ashes.

"Her glazing eyes, staring out of death to shake and bend my soul. On me

alone. The ghostcandle to light her agony. Ghostly light on the tortured face.

Her hoarse loud breath rattling in horror, while all prayed on their knees.

Her eyes on me to strike me down. Liliata rutilantium te confessorum turma

circumdet: iubilantium te virginum chorus excipiat.

"Ghoul! Chewer of corpses"

The last exclamation is characteristic. To Stephen God is the dispenser of death,

dio bòia, hangman God, as "the most Roman of catholics"

call him. His blasphemy is the cry of a panic fear, fear of the Slayer, whose

sword is lightning, which reaches its climax in the episode of the Oxen of

the Sun where a black crash of thunder interrupts the festivities at the

house of birth.

The sacral bowl of lather, in mockery elevated by

(1) Mulligan's.

(2)Agenbite of Inwit (remorse of conscience) is the title of a fourteenth century

work, by Dan Michel of Northgate.

107

Mulligan (1) becomes a

symbol of sacrifice and is linked in Stephen's mind with his mother's death

and the round expanse of bay at which he gazes from the summit of the tower.

"The ring of bay and skyline held a dull green mass of liquid. A bowl of

white china had stood beside her deathbed holding the green sluggish bile which

she had torn up from her rotting liver…" And, later, when a cloud

begins to cover the sun slowly, shadowing the bay in deeper green, "it

Iay behind him, a bowl of bitter waters. Fergus' song: I sang it alone in the

house, holding down the Iong dark chords. Her door was open: she wanted to hear

my music. Silent with awe and pity I went to her bedside. She was crying in

her wretched bed. For those words, Stephen: Iove's bitter mystery."

And no more turn aside

and brood

Upon love's bitter mystery

For Fergus rules the brazen cars...

98