the Books at the Wake

A Study of Literary allusions in

James Joyce's FINNEGANS WAKE

By James S. Atherton

Introduction

'An argument follows' (222.21)

Perhaps

- this must be the first word on such a subject - a final literary evaluation

of Finnegans Wake will never be made, for such evaluation must follow and be

based upon a complete understanding of the book. No such understanding

has yet been reached and none seems to be in sight in spite of the increasing

flow of illustrative material. The article on James Joyce in the current edition

of the Encyclopaedia Britannica correctly describes Finnegans Wake as 'the extreme

of obscurity in modern literature', and might have added that it is not only

extreme obscure but extremely long. Joyce worked at it for over seventeen years,

often spending more than fourteen hours a day in composition and revision. To

read through the book once is a full-time occupation for a week, providing that

the reader is prepared to continue reading without pausing to consider the meaning

of the words before him. If he does stop to consider there is no limit to the

time he may spend; indeed Joyce claimed that he expected his readers to devote

their lives to his book. Since its first publication in 1939 several hundreds

of articles and over thirty books have appeared explaining its profundities

from various viewpoints and in varying ways, but agreement has still not been

reached on many fundamental points. Indeed as research continues more complexities

are found and a considerable amount of odium ideologicum seemPerhaps - this

must be the first word on such a subject - a final literary evaluation of Finnegans

Wake will never be made, for such evaluation must follow and be based upon a

complete understanding of the book. No such understanding has yet been reached

and none seems to be in sight in spite of the increasing flow of illustrative

material. The article on James Joyce in the current edition of the Encyclopaedia

Britannica correctly describes Finnegans Wake as 'the extreme of obscurity in

modern literature', and might have added that it is not only extreme obscure

but extremely long. Joyce worked at it for over seventeen years, often spending

more than fourteen hours a day in composition and revision. To read through

the book once is a full-time occupation for a week, providing that the reader

is prepared to continue reading without pausing to consider the meaning of the

words before him. If he does stop to consider there is no limit to the time

he may spend; indeed Joyce claimed that he expected his readers to devote their

lives to his book. Since its first publication in 1939 several hundreds of articles

and over thirty books have appeared explaining its profundities from various

viewpoints and in varying ways, but agreement has still not been reached on

many fundamental points. Indeed as research continues more complexities are

found and a considerable amount of odium ideologicum seems to be arising between

the chief exegetes.

Even the basic plot or groundwork of the book has not been established with

certainty. The mot influential early attempt to explain the Wake to the reading

public was Edmund Wilson's article 'The Dream of H.C.Earwicker' afterwards published

in The wound and the Bow. (1) 'Wilson said that the whole book

was an account of a dream by a drunken publican in Chapelizod. Joyce remarked

at the time in a letter to Frank Budgen, which has only been published (2)

that Wilson

(1) Edmund Wilson,

The Wound and the Bow. See Bibliography

(2) Stuart Gilbert, (Editor), The Letters of James Joyce. London: Faber

and Faber, 1957,p405. Letter dated 'End July 1939'. New York: Viking

11

makes some curious blunder, e.g. that the 4th old man is Ulster'. But he did

not suggest that Wilson was wrong in anything except minor details. Wilson's

interpretation was probably the best possible at that time with the information

then available, and has been followed by many critics including Campbell and

Robinson whose A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake (1)has

provided the basis for much subsequent work, but it does not provide a satisfactory

explanation of the Wake as a whole. Indeed Professor Harry Levin whose book,

James Joyce, a Critical Introduction, remains in many ways the

best introduction to Joyce's world, puts the problem with his usual succinctness

when he says 'these orbiter dicta cannot be traced, with any show of

plausibility, to the sodden brain of a snoring publican. No psychoanalyst could

account for the encyclopedic sweep of Earwicker's fantasies.(2)

Professor Francis I. Thompson, one of the many American scholars who have devoted

a great deal of time to Joyce's work, has suggested (3) that all

Joyce's books are essentially autobiographies, and that, although 'Perhaps there

is an occasional identification of the dreamer with H.C.E.', he is usually 'James

Joyce alias Stephen Dedalus'. Louis Gillet, who was friendly with Joyce during

the years in which the Wake was being written, quotes Joyce as saying that 'Finnegans

Wake had nothing in common with Ulysses-c'est le jour

et la nuit'. (It is the day and the night) But Gillet concludes his

book with the remark that 'au fond M. Joycen'a écrit qu'un seul livre,

ou, si l'on préfère, differents états du même texte'.(4)

(at bottom M. Joyce hasn't wrote only one book, or if you prefer, different

states of the same text )Perhaps Oliver St. John Gogarty can be said to

be subscribing to the same theory when he rernarks in his book, Rolling Down

the Lea, that the 'moderns were Ieft to talk to themselves for want of an audience.

Joyce went one further and talked to himself in his sleep:

hence Finnegans Wake'.(5) It is more likely, however,

that Gogarty simply meant to say that the Wake was nonsense, although

earlier in the same book he had written of 'Joyce who loves the Liffey and wrote

about its rolling as no other man could.'(6)

This theory that Joyce is the dreamer has a great deal to recommend it; and

still more evidence has lately been brought forward in its favour

(1) Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key

to Finnegans Wake. London: Faber and Faber, 1947.

(2) Harry Levin, James Joyce, a Critical Introduction. London:

Faber and Faber, p. 124.

(3) Francis I. Thompson, 'A Portrait of the Artist Asleep,' The W/estern

Review, XIV, 2950, pp. 245-53.

(4) Louis Gillet, Stèle pour James Joyce. Marseilie: Sagittaire,

1941, p. 180.

(5) Oliver St. John Gogarty, Rolling Down the Lea. London: Constable

& Co.,2950, p. 117.

(6) Ibid, p. 8.

12

by Patricia Hutchins, who has spent several years travelling around Europe to

visit the various places where Joyce lived in order to obtain more information

about him. She has listed in her latest book, James Joyce's World,(1)

a large number of biographical details of which traces can be found in the Wake.

For example, the addresses on the 'Letter, carried of Shaun, son of Hek, written

of Shem, brother of Shaun,' (420.17) (2) turn out to be addresses

at which Joyce himself had lived, or at which his relations had lived. 7 Streetpetres.

Since Cabranke' (420.35) is ', St. Peter's Terrace, now Peter Street, Cabra,

where Mis. May Joyce died. 'Finn's Hot.' (420.25) is Finn's Hotel where, as

Patricia Hutchins tells us,(3) 'according to one account' Nora

Barnacle, who later became Joyce's wife, worked for a while in Dublin. So many

details concerning Joyce's life have been noticed by Patricia Hutchins that

she mentions the suggestion which has occasionally been made that Finnegans

Wake is a kind of confession. This suggestion is supported by the use

Joyce makes in the Wake of various famous books of 'Confessions',

St. Augustine's, Rousseau's, James Hogg's Journal and Memoirs of a Justfied

Sinner, and so on. But in addition to biographical details which have

already been pointed out iii print there are a great number of others which

the various commentators have either not known or not found room for. For example,

Joyce usually wore a hat made by the Italian firm of Borselino. This firm and

its products figure frequently in the Wake (4) and it is not impossible

that there is a hidden implication that much of the action is taking place under

the hat upon the head of James Joyce.

The full transcription is interrupted because from there on, Prof. Atherton follows the tradition of the Ivory Tower of classification according to the prevailing standards, which although valid at any time, are subject to the "fad" or the elected scholars. I will stick to observations that seems to me will help our objective, which although the same of Prof. Atherton, have the benefit of more than 50 years of criticism and Internet.

Prof. Atherton discusses the characters and whether what kind of novel Finnegans is. His observation about Joyce's attitudes towards the book which can be summarized as:

High and earnest sense of dedication.

He considered himself as the Vates, poet and prophet and his book of a new religion

of which he was prophet and priest.

He was superstitions about the power of his words

He could do anything he wanted with language

He believed he was performing some kind of magic

At the

end I will elaborate more, but for the moment it should be stressed that this

new religion he founded has its salvation in understanding what was behind this

words he used.

It is remarked again that it is perhaps impossible to know what Finnegans Wake

is all about, and Beckett 's famous observation: "it is not about something".

It is that something itself.

It

is needed now to branch out to Wikipedia and understand what was behind Working

in Progress that was the name of Finnegans when Joyce was still writing it.

These twelve Marshalls could well be described as the twelve apostles of this

new religion, although Prof.Atherson never had said that…

Follows various explanations Joyce gave to scholars and specially Miss Weaver, that lacks classification, but extremely keen, because she was liberated from the Ivory Tower standard attitude and procedures and she stated:

…My view is that Mr. Joyce did not intend the book to be looked upon as the dream of any character, but that he regarded the dream form with its shiftings and chances and chances as a convenient device, allowing the freest scope to introduce any material he wished - and suited to a night-piece.

She also informed to Professor Joseph Prescott in a letter:

"In the summer of 1923 when Mr. Joyce was staying with his family in England he told me he wanted to write a book which should be a kind of universal history and I typed for him a few preliminary sketches he had made for isolated characters in the book"

When Miss Weaver complained to Joyce that she could not understand the extracts she was typing for him he replied, "I am sorry that Patrick and Berkeley are unsuccessful in explaining themselves. The answer, I suppose, is that given by Paddy Dignam's apparition: metempsychosis. Or perhaps the theory of history so well set forth (after Hegel and Giambattista Vico) by the four annalists who are even now treading the typepress in sorrow will explain part of my meaning. I work as I can and these are not fragments but active elements and when they are more and a little older they will begin to fuse of themselves."

The bottom line is that the book

in fact is a novel about one man and his family which becomes a history of mankind.

Which is the outcome of two things: Joyce's life and Joyce's readings

For those who which to become members

of this religion, first be wise up because the writing has several planes of

meaning, every sentence has several connotations, second, look for the help

of his biographers, because it is autobiographical, third Joyce's reading was

extraordinarily wide and Prof. Atherton is specially concerned with this aspect.

He explains how he dealt with that, and it has to be read in his book and I

cannot help but to observe that he did singlehandedly what Internet offers to

everybody, and even with this gigantic help he produced a masterpiece.

the end I will elaborate more, but for the moment it should be stressed that this new religion he founded has its salvation in understanding what was behind this words he used.

It is remarked again that it is perhaps impossible to know what Finnegans Wake is all about, and Beckett 's famous observation: "it is not about something". It is that something itself.

It is needed now to branch out to Wikipedia and understand what was behind Working in Progress that was the name of Finnegans when Joyce was still writing it.

These twelve Marshalls could well be described as the twelve apostles of this new religion, although Prof.Atherson never had said that…

Follows various explanations Joyce gave to scholars and specially Miss Weaver, that lacks classification, but extremely keen, because she was liberated from the Ivory Tower standard attitude and procedures and she stated:

…My view is that Mr. Joyce did not intend the book to be looked upon as the dream of any character, but that he regarded the dream form with its shiftings and chances and chances as a convenient device, allowing the freest scope to introduce any material he wished - and suited to a night-piece.

She also informed to Professor Joseph Prescott in a letter:

"In the summer of 1923 when Mr. Joyce was staying with his family in England he told me he wanted to write a book which should be a kind of universal history and I typed for him a few preliminary sketches he had made for isolated characters in the book"

When Miss Weaver complained to Joyce that she could not understand the extracts she was typing for him he replied, "I am sorry that Patrick and Berkeley are unsuccessful in explaining themselves. The answer, I suppose, is that given by Paddy Dignam's apparition: metempsychosis. Or perhaps the theory of history so well set forth (after Hegel and Giambattista Vico) by the four annalists who are even now treading the typepress in sorrow will explain part of my meaning. I work as I can and these are not fragments but active elements and when they are more and a little older they will begin to fuse of themselves."

The bottom line is that the book in fact is a novel about one man and his family which becomes a history of mankind.

Which is the outcome of two things: Joyce's life and Joyce's readings

For those who which to become members of this religion, first be wise up because the writing has several planes of meaning, every sentence has several connotations, second, look for the help of his biographers, because it is autobiographical, third Joyce's reading was extraordinarily wide and Prof. Atherton is specially concerned with this aspect.

He explains

how he dealt with that, and it has to be read in his book and I cannot help

but to observe that he did singlehandedly what Internet offers to everybody,

and even with this gigantic help he produced a masterpiece.

Part I The Structural Books

A large class from which few words

have been taken.

A smaller class from which not only words have been taken, but also ideas.

Basic features of how these books were amalgamated are:

1- Uniqueness of style

2- Uniqueness of structure

3- Interior logic of the book

Fundamental assumption is that Joyce is God-like when God is performing his task of creation, surrogating God as His substitute. He does that creating another scripture. Joyce's scripture is built on premises of its own, although drawing basically from the following concepts:

-

Vico's cyclic view of history

- Primitive psychology as theorized by Lévy-Bruhl

with the aid of Giordano

Bruno, Nicholas

of Cusa and some Freud

- Mixed with Arthur

Symons idea of style as explained in his book, The

Symbolist Movement in Literature under influence of Mallarmé

and Pound's central

idea that every word must be fully charged with meaning.

- Tempering all that using Wagnerian

operas, some other musical techniques and painters theories.

- Cook to the point over the fire of constant and unwearying experiment.

On top of that Joyce assumes that

the reader although no necessarily having to have read all these source books,

would know the axioms Joyce took from them.

These axioms are the clues and perhaps the most important task Prof Ataherton

does is to identify them. Some of these axioms:

From Vico

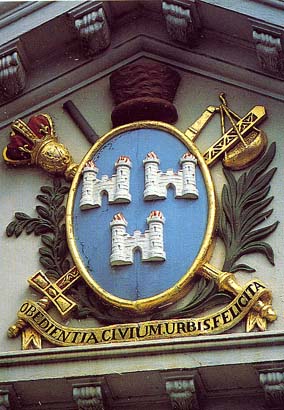

Besides Vico's cyclic view, he added the idea of a Thunder each time men, in whichever state of evolution, felt, similarly as Adam from Paradise. The Thunder is the Voice of God. Vico's metaphor that the first men "giants" dragged their women into caves for protection against the God of Thundering Sky and so invented matrimony and the necessary order. Coincidence or not, Vico comes very close in quoting the motto of the city of Dublin: Obedientia civium orbis felicitas, which Joyce took happily over. (The obedience of citizens is the happiness of a city").

The Thunder was the Voice of God and first men were mute, communicating through gesture. To utter sound, like God, was perhaps blasphemous, because was an imitation of the voice of the thunder. At the beginning they stutter and so Joyce does when emulating that. There is an elaborate theory connecting stuttering with consciousness of guilty and basically it is a symbol for the fall from paradise in Genesis, which has equivalent stories elsewhere.

The fall and an Angry God Shouting at the sinner is a recurrent constellation in Joyce's work and I would dare to say if it was psychoanalysis it is his problem state.Joyce evem made God stutter in a clear attempt to simulate a God which is conscious of having committed a sin! The idea of atribution of the Original Sin to God is one of the basic axioms of Finnegans Wake. The Original Sin is a poor explanation to the existence of Evil as it is well known, but it is the oficial catholic solution to the problem. It is not absurd as it seems, because as Prof Atherton puts so well, and I quote:

In every small boy's household when the father of the family is enraged. And serenely behind the outraged father there rests-in Joyce's version - the mother-figure, Anna Livia. She is always calm, and always right. It is, indeed, to be regretted that her neighbours tell strange stories about her; but unlike her husband, who is constantly stuttering his apologies, she is aware of her virtue. This is a typical situation. It is not the autobiographical details that concern us here but the structural formulae. And from what has been said so far it can, I think, be laid down that the following axioms from Vico apply to Finnegans Wake.

1. History is a cyclic process repeating

eternally certain typical situations.

2. The incidents of each cycle have their parallels in all other cycles.

3. The characters of each cycle recur under new names in every other cycle.

4. Every civilization has its own Jove.

(thunder)

5. Every Jove commits again, to commence his cycle, the same original sin upon

which creation depends. It would appear to follow from this that creation is

the original sin.

Joyce

repudiates once more the Christian explanation for the original sin in a very

confusing way that even Prof Ataherton confessedly misinterpreted, and I quote:

Professor W. Y. Tindall has already

pointed out that 'All three of Vico's languages appear in Finnegans Wake'.

(1) According to Vico the three kinds of language were first,

'A divine mental language by mute religious acts or divine ceremonies... And

it was necessary in the earliest times when men did not yet possess articulate

speech...The second was by heroic blazonings with which arms are made to speak;

this kind of speech. . . survived in military discipline. .. The third is by

articulate speech which is used by all nations.'(2) Not realizing

the use that Joyce was making of this statement by Vico I wrongly said in an

article about Lewis Carroll and Finnegans Wake that by 'middle' and 'ancient

tongue' Joyce meant simply Middle Egyptian. It is always unwise to say that

Joyce only means one thing, practically every word in the Wake

has at least two meanings, and it is now apparent to me that heraldry is also

a middle ancient tongue and that the passage in which the phrase occurs is concerned

with heraldry as well as with Middle Egyptian. The passage runs: 'To vert embowed

set proper penchant. But learn from that ancient tongue to be middle old modern

to the minute. A spitter that can be depended upon. Though Wonderlawn's lost

to us forever. Alis, alas, she broke the glass! Liddell lokker through the leafery,

ours is mistery of pain' (270.16). 'Vert' and 'Proper' are terms from heraldry

brought into the Wake because it is Vico's 'Middle language'. Alice Liddell,

Carroll's Alice, is portrayed as being an Eve before the Fall. We, coming after

the Fall, have the mystery of pain, which has just been discussed. But Joyce

is repudiating the Christian explanation and brings in the Ancient Egyptian

creation myth of Atem who populated the world by spitting on the fertile mud.

('Take your mut for a first beginrun Anny iiffle mud. . . will doob') (287.5).

Other versions of this creation myth say that the first pair of gods, Shu and

Tefnut, were begotten from the primeval mud pile by Atem's self-abuse.(3)

This, of course, takes us back to the theory that the original sin was

God's.

(1) W. Y. Tindall,

James Joyce, His Way of Interpreting the Modern World. London: Charles

Scribner's Sons, Ltd., 1950, p. 74.

(2) Vico, p. 69.

(3)See below in the chapter on 'The Sacred Books'.

Heraldry

House

of Savoy FERT Fortitudo eius Rhodum tenuyit, Foemina erit ruina tua

- (His strength conquered Rhodes, Women will destroy you)

Etymology

Another thing Joyce took from Vico, in addition to his cyclic theory of history and his theory of language, was his way of using etymology. According to Vico the course of history could be inferred from etymology since the story of man's progress was embedded in the structure of the words we use. In Finnegans Wake words are constructed so as to contain within themselves sufficient data to allow the structure of the entire work to be deduced from any typical word.

Using concepts expressed by Edgar Quinet in his Introduction à la Philosophie de l'Histoire de l'Humanité, which is based in Vico's theories, Joyce assumed that Finnegans is the "ideal eternal history", for Finnegans Wake can be taken as being the story of one man, or one family, or of one city or country, or of all humanity and the entire course of history, since all these are progressive expansions of one story.

From Nicholas of Cusa

Coincidence of contraries and learned ignorants.

From Giordano Bruno

Bruno and Nicholas of Cusa alike

believed in the coincidence of contraries. Joyce uses this theory to strange

effect in Finnegans Wake where, for example, an arguing pair like Butt and Taff

can suddenly become 'one and the same person' (354.8) because they are 'equals

of opposites . . . and polarised for reunion by the symphysis of their antipathies'

(92.8). Bruno also stated in his Of

the Infinite Universe and Innumerable Worlds that 'The actual and

the possible are not different in eternity.'(2) It is from this

that Joyce derives his assumption that the events and characters described in

history, literature and myth have equal validity. Maria Martin, Hamlet and the

Duke of Wellington are characters of the same kind. Bruno also maintained that

each thing contained the whole. By this he seems to have meant that the universe

is made up of separate entities each constituting a simulacrum of the universe.

This was a fairly common medieval theory and provides another source for the

axiom already suggested that in Finnegans Wake each individual

word reflects the structure of the entire book. Bruno's theories went much further

and suggest several other possible axioms governing the construction of the

Wake. He claimed that there was an infinite number of entities

ranging in value from the minimum to the maximum-which was God; and that each

entity except the last was continually changing and not merely by becoming greater

or less but by exchanging identities with other entities. This suggests the

behaviour of characters and words in the Wake where every part tends to change

its identity all the time.

Bruno's name is mentioned over a hundred times in the Wake, much more often

than any other philosopher's. As has been frequently pointed out he is usually

personified as the firm of Dublin booksellers, Browne and Nolan. This is probably

because of his habit of referring to himself in his writings as 'il Nolano'.

Professor Tindall has pointed out that 'Tristopher and Hilary, the twins of

the Frankquean legend, get their names of sadness and joy from Brkuno's motto:

In tristitia hilaris hilaritate tristis -Pensive

sadness cheerful cheerfulness

(2) John Toland, A Collection

of Several Pieces with an Account of Jordano Bruno’, Of the Infinite Universe

and Innumerable Worlds. London, 2726, p. 322.

From Freud

and Jung

Prof. Atherton ellaborates what can be better clarified from material that only would be available long after:

What Joyce really thought? From a review of his letters

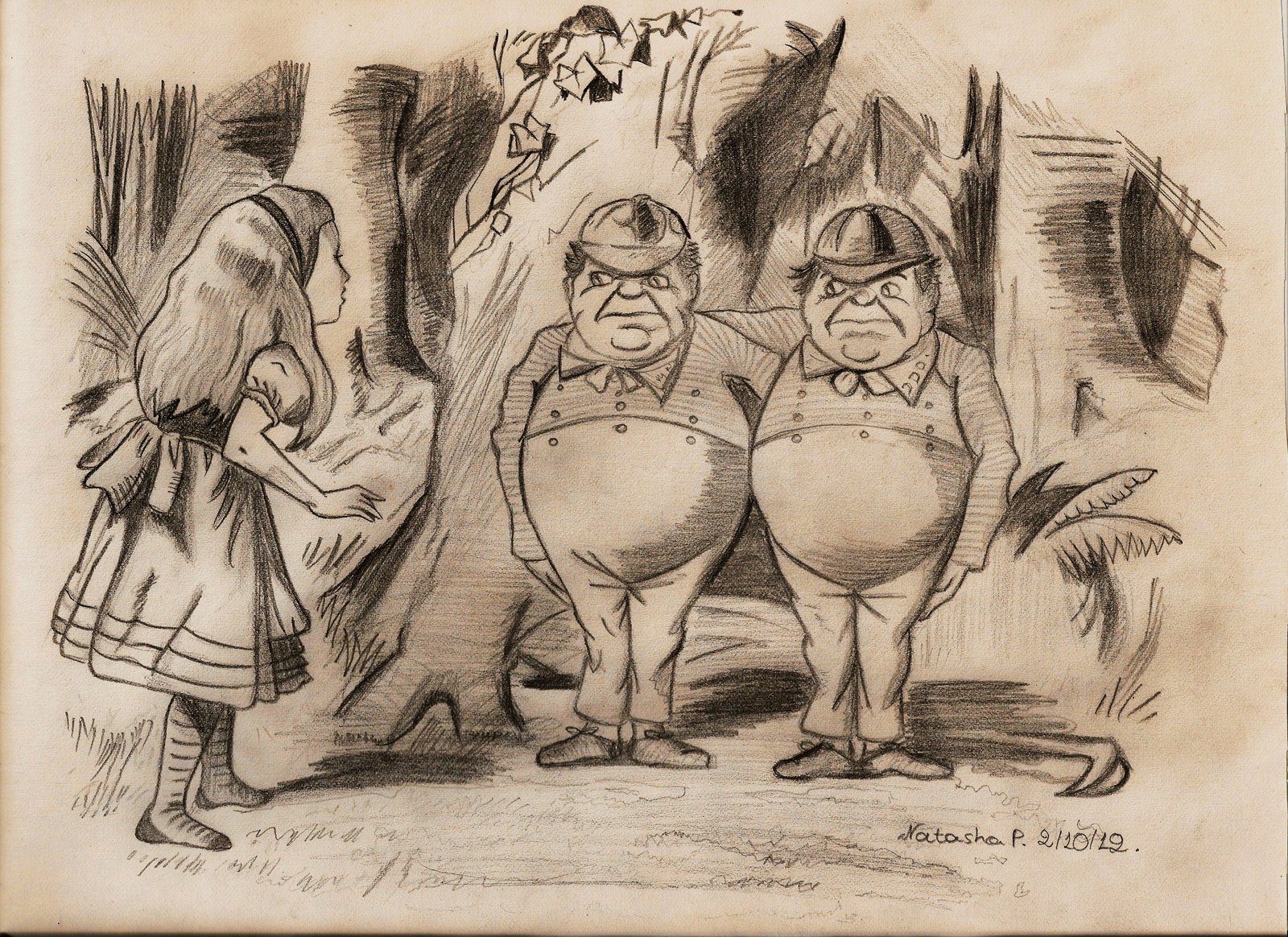

Of Jung and Freud, he writes (June, 1921): "A batch of people in Zurich persuaded themselves that I was gradually going mad and actually endeavored to induce me to enter a sanatorium where a certain Doctor Jung (the Swiss Tweedledum who is not to be confused with the Viennese Tweedledee, Dr. Freud) amuses himself at the expense (in every sense of the word) of ladies and gentlemen who are troubled with bees in their bonnets."

What happened to Joyce`s daughter and what Jung did

Mrs. Talbot is daughter of Prof. Atherton and there is a lot of information about him and how he was doing this book we are studying, besides, obviously, Lucia Joyce.

From Morton Prince

His book, The Dissociation of a Personality seems to have played an important role in the approach Joyce did in the way he splited many characters in his book.

It is amazing that Prof. Atherton dedicated only a couple of pages on the subject, because it seems to me that the one element missing to close out the question of What Finnegans is all about has to do a lot with that. Since the method I have chosen to figure out that passes through a review of what eminent minds have to say about it and I intend to close it out with my appreciation, I will elaborate more on that at the conclusion of this job.

From James Hogg

His book Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner also played a role in Joyce`s dealing with opposites. You can read it.

From Lévy-Bruhl

Joyce had at his 'personal library' at Buffalo, NY, two books from Lévy-Bruhl: L'Experience Mystique et les Symboles chez les Primitifs and L'Ame Primitive . Joyce used extensively his theories, although in Finnegans he attacked him, joking about him.

From the Occultists

As we can see in the Webster's Dictionary, occult theory or practice : belief in or study of the action or influence of supernatural or supernormal powers.

This is a standard effect in learned people when the relinquish their religions, specially if they were Christians or catholics. Bertrand Russel pointed out about that effect in Joyce when he said: "The first effect of emancipation from the Church was not to make men think rationally, but to open their minds to every sort of antique nonsense" (In A History of Western Philosophy,London, 1946, page 523.

I was amazed to realize, when doing research about Joyce in the ammoutn of scholars that fit to this description, including many PhD's Thesis! I will elaborate more about that in conclusion.

From Spiritualism

Conan Doyle's

Spiritualism is a pasteurization of occultism and is very popular in Brazil,

specially among intellectuals. This is also a key notion to understand Joyce

which will be also elaborated at conclusion.

From Arthur Symons

Very interesting observation by Prof. Atherton:"... it seems to me very probable that the major source (of influence on Joyce) is not Mallaarmé but Symons account of Mallarmé." Quoting from Prof. Atherton:

"The fact that Joyce copied

down Symons's translation into his notebook instead of MalIarmé's own

words proves, I think, that this contention is true.

It would be in Symons's The

Symbolist Movement that Joyce found the formula, first laid

down by Mallarmé, which he was to use in writing Finnegans Wake: 'To

evoke, by some elaborate, instantaneous magic of language, without the formality

of an after all impossible description; to be rather than to express.' (5)

This is precisely what Beckett said about Joyce's writing: 'it is not

about something; it is that something itself;' (6), as Beckett knew,

this was one of the principal aims of the Wake:

'to be rather than to express'. 'Imagine the poem already written down,'

continues Symons, 'the work has only begun. . . Pursue this manner

of writing to its ultimate development; start with an enigma and then withdraw

the key to the enigma.'(7) This corresponds to the way Shem had of writing

'about all the other people in the story, leaving out, course, foreconsciously,

the simple worf;' (174.1), and I think it is t method employed by Joyce in writing

Finnegans Wake. Certainly it is typical of his methods that 'the quotation most

obviously relevant to the situation' is, as M. J. C. Hodgart was the first to

point out, (1) always carefully omitted." (page 49-50)

(5) Symons, p.130

(6) An Exagmnation, p.14 (Beckett's italics).

(7) Symons, p.134

(1) M.J.C. Hodgart, 'Work in Progress', The Cambridge Journal,

Vol VI, no. I, .29

From ... Words

Prof. Atherton did not separated an axiom for Words, but he might very have done... And it should be placed at page 51 in the second paragraph, which I quote:

"Joyce's

main interest was in words; his second interest was theology; it

is difficult to say which interest was pursued by him to the greater excess

of idiosyncrasy. It has often been said that in writing Finnegans Wake he set

out to create for himself a new language.(2) On the other hand

many critics have protested that 'James Joyce Wrote English',(3)

as Walter Taplin entitled an essay on this subject, and I think that this is

true. What Joyce did try to create was a complete philosophical system. It is

interesting in this context to consider a remark he once made to Frank Budgen.

He was speaking to Budgen of the things which women have done, and he ended,

'It brings me to this point. You have never heard of a woman who was the author

of a complete philosophical system. No, and I don't think you ever will.' (4)

It appears from this that Joyce felt that such a system was a special

mark of the superiority of the male; and I have no doubt that he believed that

he had created such a system himself. The last recorded description he gave

of the Wake Was 'the great myth of everyday life'. (5) This was

in an interview with a Polish journalist named Jan Parandowski whom he told

that he had taken literally Gautier's motto: L'inexprimable

n'existe pas. I am suggesting that he took a number of other mottoes

as bases, and said nothing about them.

The most obvious of these is Pound's frequently repeated statement that: 'Good

literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.'

"

(1) Symons, p. 28.

(2) E.G. Jolas in An Exagmination, p. 89: 'Language is being born

anew before our eyes.' McGreevy, ibid., p. 520: 'In spite of the difficulty

of having to invent a new language as he writes'.

(3) Walter Taplin, 'James Joyce Wrote English', The Critic, Spring,

1947, p. 12.

(4) Frank Budgen, Further Recollections of James Joyce. London:

The Shenvall Press, 1955, p. 6.

(5) Jan Parandowski, 'Begegnung mit Joyce', Die Weltwoche. Zürich,

i rth Feb. 1949.

From ... Painters

Prof. Atherton did not also separated an axiom for painters, but he might very have done also... And it should be placed at page 52 in the second paragraph, which I quote:

"The Wake puts this into practice

to an extent which might well be held to disprove it. But Manifestoes and statements

of artistic Credos were in the air. Joyce spent his most creative periods in

cities containing groups of painters who were fertile in devising theories of

art and culture which they put into words as clear and comprehensible as their

paintings were difficult and mysterious. In this latter aspect they resembled

Joyce, and I do not think that the resemblance is simply a coincidence; more

probably it results from their following similar lines of thought, although

Joyce's range was, I think, wider.

There are several axioms proposed by painters which Joyce may perhaps have used.

Chevreul, for example, the 'heresiarch of cubism', wrote

that 'I have had the idea of suppressing the images one sees in reality, the

objects which have the effect of corrupting the hierarchy of colour.' This is

what-as we have seen-Joyce called 'leaving out... the simple worf'; and, as

applied to colour, is one of the ideas which Joyce is playing with in the 'topside

joss pidgin feila Balkelly' (611.4) passage. There was also Larionov, who-as

long ago as 1910-declared his aim to be a new combination of space-time. More

important, for the Wake, is Paul

Klee, whose name Joyce puns on in many passages containing variants

of the word key. The phrase 'arpists at cloever spilling' (508.33) includes

Klee's name along with Hans

Arp's, and puns on clover/clever for Arp's experiments in poetry

with distorted spellings. Klee announced that the most vital aim of the artist

was to create new 'possible worlds'; Joyce seems to have applied himself to

this aim with his usual thoroughness, and-from internal evidence in the Wake-it

seems that he knew of Klee's theories, and probably found them useful to combine

with Bruno's

concept of innumerable worlds."

I did research on the subject and managed a more comprehensive idea on the subject

Here, then, to summarize, what appears to be the main axioms of the Wake:

I - The Structure of History. (Vico)

a. History is a cyclic process repeating

eternally certain typical situations.

b. The incidents of each cycle have their parallels in all other cycles.

c. characters of each cycle recur under new names in all other cycles.

II. The Structure of the Universe. (Vico, Bruno, Nicholas of Cusa, Klee)

a. There are an infinite number of

worlds. (Bruno, Klee.)

b. As each atom has its own individual life (according to Bruno) so each letter

in Finnegans Wake has its own individuality.

c. Each word tends to reflect in its own structure the structure of the Wake.

(Bruno, the Cabbala.)

d. Each word has 'a predestined ambiguity' (Freud), and a natural tendency to

slide into another state (Bruno).

e. Characters, like words, not only transmigrate from era to era (Vico and Bruno),

but also tend to exchange their identities. This is most marked when they are

opposites (Nicholas of Cusa).

III. Number. (Lévy-Bruhl, Nicholas of Cusa, the Cabbala)

a. Unity and diversity are opposed

states each constantly tending to become the other. (Nicholas of Cusa.)

b. Duality is the most typical form of plurality. Two of a kind therefore represent

all of that kind. (Lévy-Bruhl.)

c. Numbers have a magical, not an arithmetical significance. (The Cabbala.)

The numbers one to twelve also indicate certain characters or groups of characters.

Certain numbers (e.g. 1132) have special magical properties.

IV. Theology. (Vico, Bruno, Budge's notes to The Book of the Dead)

a. Original sin was committed by

God. It is simply the act of creation.

b. 'Each civilization has its own Jove.' (Vico.)

c. Each Jove commits again, in a new way, to commence his cycle, the Original

sin on which creation depends.

V. Style. (Symons, Mallarmé, the theory of music, Pound)

a. 'Every word must be charged with

meaning to the utmost possible degree.' (Pound.)

b. 'It is the aim of language to approximate to music.' (Pater.)

c. Musical techniques can therefore be applied in the Wake. The Wagnerian leit-motiv,

and the concept of 'Voices' in polyphony are frequently used.

d. Since the book is a whole all parts must cohere.

VI. Language. (Vico, Freud, Gautier, Jousse)

a. 'Everything can be expressed.'

(Gautier.)

b. In its portrayal of the ideal eternal history the Wake must use the three

forms in which language developed. These are:

1 Symbolic acts, gesture. (Vico, Jousse.)

2. Heraldry. (Vico.)

3. Human speech.

This last evolves from the attempts

of men to reproduce the voice of thunder. Their first attempts were stuttering.

(Vico.)

c. Stuttering indicates guilt. (Freud, Carroll.)

d. As words contain in themselves the image of the structure of the Wake they

also contain the image of the structure of history. (Bruno.)

e. Thundering, being itself a kind of stuttering is an indication of guilt.

VII. Space-Time.

Joyce's experiment in creating what

Larionov called 'a new combination of space-time' has been left to the end of

this section because I am neither confident of the correctness of my interpretation

nor aware of any literary sources for Joyce's methods. My suggestion is that

Joyce's four old men represent in the first place Space, being geographically

the four points of the compass and literally the first four letters of the Hebrew

alphabet-thus standing for all the other letters and so representing literary

space. They have, of course, many superimposed qualities, such as their identification

with Swift's Struldbrugs, who were impotent immortals. But they acquire these

extra personifications because they are primarily Space. They represent the

four walls of the room and the four posts of the bed, watching impotently and

enviously the actions of the ever-changing figures that occupy the space between

them. They are Aleph, Beth, Ghimel and Daleth, eternal beings:

'semper as oxhousehumper' (107.34) gives us the English meaning of their names-ox,

house, camel; Daleth, the door, is named in 'till Daleth, mahomahouma, who oped

it closeth thereof the. Dor' (20.17). As letters they are the 'fourdimmansions'

(367.27); as points of the compass 'the bounds whereinbourne our solied bodies

all attaim arrest' (367.29). Their order is unchangeable: North, South, East

and West. It is probably from the old prayer 'Matthew, Mark, Luke and John,

bless the bed that I lie on', that they become also the evangelists for they

are still in the same order. As the four provinces they occur invariably as

Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connaught; never getting out of their order of

precedence, and usually even speaking that order. But I think it is as circumambient

space that they are really important. They have been there all the time and

know everything that has happened. That is why we can be told that 'the quad

gospellers may own the targum' (112.6) when the difficulty of understanding

the Wake is being discussed, for the Targum is the book which explains the Old

Testament and they were there when the events described in the Old Testament

took place.

This account of Joyce's personification of Space may be completely wrong; but

it seems to me to make sense of much that is otherwise comprehensib1e if my

theory is accepted. But for my interpretation of Joyce's treatment of Time I

have less confidence. Time is, I think, personified by Tom, the manservant who

brings things and takes them away. His name is also Tim which is what we dial

in England to find the time by telephone. He is sometimes 'tompip' (178.27)

which suggests the 'time-pip' given by the B.B.C. His name mutates into Atem

and so on, for Time is a sort of God in that it puts a period to our lives.

Tom Tompion, the watchmaker (15 1.18), provides the typical link that Joyce

always seemed able to find between his fantasy and history. All I can really

affirm with confidence, however, is that if Tom is Time a number of mysterious

things in the W7ake become a little less mysterious. And that is all that can

be said for most of my suggestions.