QUADRATURE

Crossroads and Borderlines

L'oeuvre Carrefour/l'oeuvre Limite

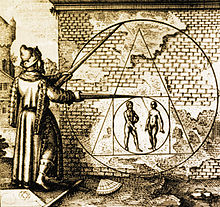

Jung explains it as follows:

[...] the squaring of the circle was a problem that greatly exercised medieval minds. I is a symbol of the opus alchymicum, since it breaks down the original chaotic unity into the four elements and then combines them again in a higher unity. Unity is represented by a circle and the four elements by a square. The production of one from four is the result of a process of distillation and sublimation which takes the so-called "circular" form: the distillate is subjected to sundry distillations so that the "soucl" or "spirit" shall be extracted in its purest state.

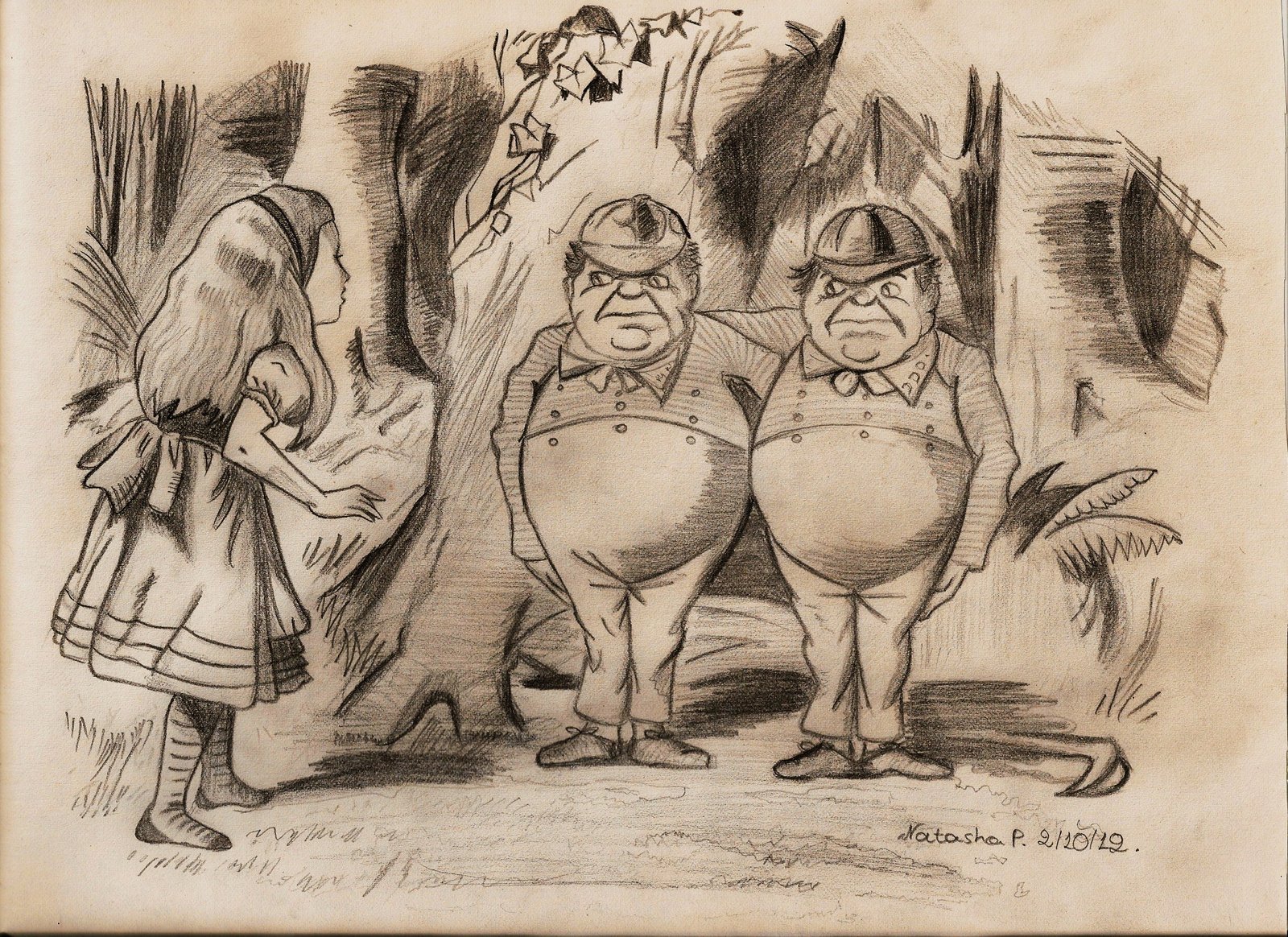

That is the quadrature of a circle is the way from chaos to unity, the method by which four elements represented by a square can reach a higher unity in the circular firms. In his explanation of the dream, Jung further states: "the left, the sinister side, is the unconscious side. Therefore a leftward movement is equivalent to a movement in the direction of the unconscious, whereas a movement to the right is 'correct' and aims at consciousness" These aspects of the mandala dream reminds us of the four players in Quad circulating leftward along the sides and diagonals of the quadrangle which is divided into four triangles. If the players' counter-clockwise pacing points in the direction of the unconscious just like the walking in the dream, what lies ate the centre of the Quad mandala?

Concerning the centre, Jung's interpretation of the dream is quite suggestive: "the dreamer is not in the centre but to one side. they say that a gibbon is to be reconstructed." The centre, then, is reserved for a "gibbon" - according to Jung, an anthropoid, an archaic human being - and so the left-hand path leads down into the bestial instinctive foundations of human existence. Therefore the reconstruction of the gibbon can be understood as an attempt "to abolish the separation between the unconscious mind and the unconscious, the real source of life, and to bring about a reunion of the individual with the native soil of his inherited instinctive make-up".

Furthermore, what is remarkable about Jung's interpretation of the mandala dreams is that he regards the mandala symbols as images of an archetypal nature which depict the centralizing process or the production of a new centre of personality. He calls this process "individuation" and this centre the "self", emphasizing that the self is not only the centre but also the whole circumference, embracing both the conscious and the unconscious. It is the centre of this totality., being different from the ego which is only the centre of consciousness. since the square particularly expresses the complete symmetry of conscious and unconscious, its centre means the unity of the self . This centre is, however, unrecognizable. As Jung observes:

Often one has the impression that the personal psyche is running round this central point like a shy animal, at once fascinated and frightened, always in flight, and yet steadily drawing nearer.

I trust I have given no cause for misunderstanding that I know anything about the nature of the "centre" - for it is simply unknowable and can only be expressed symbolically through its own phenomenology, as is the case, incidentally, with every object of experience.

The matter lies before the eyes of all; everybody sees

it, touches it, loves it, but knows it not. The

Golden Tract

The matter lies before the eyes of all; everybody sees

it, touches it, loves it, but knows it not. The

Golden Tract

---------------

The same way that Campbell is to literature what pasta is to Italian cuisine, Jung is to psychology . It doesn`t matter what you are eating, there will be always be pasta...

Jung is not easy to grasp as to what is his intent or what he or his ideas are all about. The metaphor in the figure above, which represents Jung`s ideas as described by Becket is as good as any.

But it is like one of the blind men from the Aesopus fable.

It should be remembered that we are dealing with A DREAM that is what Joyce had in mind when creating Finnegans.

For that purpose, Jung's ideas ar OK.

But for those who think they found the key to Finnegans Wake, in Jung's ideas, take a look on what Jung said about Ulysses:

"Ulysses is a book which pours along for seven hundred and thirty-five pages, a stream of time of seven hundred and thirty-five days which all consist in one single and senseless every day of Everyman, the completely irrelevant 16th day of June 1904, in Dublin — a day on which, in all truth, nothing happens. The stream beings in the void and ends in the void. Is all of this perhaps one single, immensely long and excessively complicated Strindbergian pronouncement upon the essence of human life, and one which, to the reader’s dismay, is never finished? Perhaps it does touch upon the essence of life; but quite certainly it touches upon life’s ten thousand surfaces and their hundred thousand color gradations. As far as my glance reaches, there are in those seven hundred and thirty-five pages no obvious repetitions and not a single hallowed island where the long-suffering reader may come to rest. There is not a single place where he can seat himself, drunk with memories, and from which he can happily consider the stretch of the road he has covered, be it one hundred pages or even less… But no! The pitiless and uninterrupted stream rolls by, and its velocity or precipitation grows in the last forty pages till it sweeps away even the marks of punctuation. It thus gives cruelest expressions to that emptiness which is both breath taking and stifling, which is under such tension, or is so filled to bursting, as to grow unbearable. This thoroughly hopeless emptiness is the dominant note of the whole book. It not only begins and ends in nothingness, but it consists of nothing but nothingness. It is all infernally nugatory."

"I had an uncle whose thinking was always to the point. One day he stopped me on the street and asked, “Do you know how the devil tortures the souls in hell?” When I said no, he declared, “He keeps them waiting.” And with that he walked away. This remark occurred to me when I was ploughing through Ulysses for the first time. Every sentence raises an expectation which is not fulfilled; finally, out of sheer resignation, you come to expect nothing any longer. Then, bit by bit, again to your horror, it dawns upon you that in all truth you have hit the nail on the head. It is actual fact that nothing happens and nothing comes of it, and yet a secret expectation at war with hopeless resignation drags the reader from page to page… You read and read and read and you pretend to understand what you read. Occasionally you drop through an air pocket into another sentence, but when once the proper degree of resignation has been reached you accustom yourself to anything. So I, too, read to page one hundred and thirty-five with despair in my heart, falling asleep twice on the way… Nothing comes to meet the reader, everything turns away from him, leaving him gaping after it. The book is always up and away, dissatisfied with itself, ironic, sardonic, virulent, contemptuous, sad, despairing, and bitter…"

Letter he sent to Joyce on September 27, 1932 — almost immediately after the review was published:

:Dear Sir,

Your Ulysses has presented the world such an upsetting psychological problem that repeatedly I have been called in as a supposed authority on psychological matters.

Ulysses proved to be an exceedingly hard nut and it has forced my mind not only to most unusual efforts, but also to rather extravagant peregrinations (speaking from the standpoint of a scientist). Your book as a whole has given me no end of trouble and I was brooding over it for about three years until I succeeded to put myself into it. But I must tell you that I’m profoundly grateful to yourself as well as to your gigantic opus, because I learned a great deal from it. I shall probably never be quite sure whether I did enjoy it, because it meant too much grinding of nerves and of grey matter. I also don’t know whether you will enjoy what I have written about Ulysses because I couldn’t help telling the world how much I was bored, how I grumbled, how I cursed and how I admired. The 40 pages of non stop run at the end is a string of veritable psychological peaches. I suppose the devil’s grandmother knows so much about the real psychology of a woman, I didn’t.

Well, I just try to recommend my little essay to you, as an amusing attempt of a perfect stranger that went astray in the labyrinth of your Ulysses and happened to get out of it again by sheer good luck. At all events you may gather from my article what Ulysses has done to a supposedly balanced psychologist.

With the expression of my deepest appreciation, I remain, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

C.G. Jung

Two years later Jung treated Joyce's daughter, Lucia, for schizophrenia. It was around this time that Joyce wrote in Jung's copy of Ulysses:

To Dr. C. G. Jung, with grateful appreciation of his aid and counsel. James Joyce. Xmas 1934, Zurich.

What Joyce really thought? From a review of his letters

Of Jung and Freud, he writes (June, 1921): "A batch of people in Zurich persuaded themselves that I was gradually going mad and actually endeavored to induce me to enter a sanatorium where a certain Doctor Jung (the Swiss Tweedledum who is not to be confused with the Viennese Tweedledee, Dr. Freud) amuses himself at the expense (in every sense of the word) of ladies and gentlemen who are troubled with bees in their bonnets."