The philosophical study

of what we do not know falls under the heading of nepistemology. Epistemology,

as many people will be aware, is the study of how knowledge comes into being.

Its complement, nepistemology,is the study of how ignorance becomes manifest.

Despite the extraordinary importance of nepistemology, the field has little

literature and even fewer practitioners.

Francis Bacon once wrote, truth comes out of error more rapidly than out of confusion. A clear mistake does far more good to any investigation by identifying the specific nature of the problem being addressed than any other method. Hence the trite (butt rue) aphorism that we learn best from our mistakes People who never err not only never succeed, but have no mistakes (and hence generate no problems) from which to learn

The things that are the

most interesting in terms of revealing ignorance are those that are the most

disturbing or which conflict most clearly with strongly held beliefs or practices.

Therefore, pay attention to the heretics, revolutionaries, and people stepping

to their own drummer. Many of their ideas will be wrong, but many of the problems

they reveal will be valid

In some Muslim countries, AIDS-prevention counselors are not allowed to mention the fact that AIDS is spread most commonly by homosexual men and female prostitutes because neither group may be mentioned in conversation or print. Thus, programs that have proven to be very effective in controlling AIDS in some countries cannot be used in others because of such taboos.

Socrates was put to death for the anti-social implications of his questions. Galileo was charged with heresy by the Catholic Church for daring to question the Ptolemaic view of the universe that underpinned Church doctrine.

Darwin became a pariah among fundamentalists of many religions for questioning whether God had indeed created man in His image.

Margaret Sanger and Marie Stopes, the revolutionaries who gave Western women contraceptive knowledge, each went to jail more than once. So did the many suffragettes who worked to give women the vote, simply for asking why women should not be able to do the things men do.

One must have the courage of such people in order to break the taboos that prevent most of us from asking certain types of questions or facing the consequences of certain types of answers.

The more dangerous the

questions are to people in power, the greater the courage needed to ask them.

The existence of a well-defined problem does not imply the existence of a

solution" (Benford, 1989, p. 155).

For example, many people have desired to create perpetual motion machines. The criteria defining the problem are extremely well defined: such a machine must be capable of creating more energy than it uses. Stated as a question, the problem becomes: how does one create energy de novo? Anyone who has physics knowledge knows that, while this is structurally and logically a well-formulated question, it is not a reasonable question. To create energy de novo would violate the laws of thermodynamics. Thus, despite the fact that the problem can be stated exactly, it can also be shown that the problem has no solution.

The question of whether God performs miracles is of the same class because miracles are, by definition, metaphysical or supernatural events beyond human comprehension, thereby placing any evidence beyond our ability to validate or replicate it.

Such questions are therefore beyond rational discourse and belong, properly so, to questions of faith.

Origins of

the concept what is to be intelligent

(and somewhat also what is to be non intelligent)

William M.lvins Jr, in his book Prints and visual communications, extensively quoted by McLuhan in the Galaxy of Gutenberg, and I specifically want to quote from there the following: (The Blocked Road, pags 3-20)

"From very ancient

times materials suitable for the making of prints have been available, and apposite

skills and crafts have been familiar, but they were not brought into conjunction

for the making of exactly repeatable pictorial statements in Europe until roughly

about A.D. 1400. In view of this it is worthwhile to

try to think about the situation as it was before there were any prints.

As it seems to be the usual custom to begin with the ancient Greeks when discussing

anything that has to do with culture, I shall follow the precedent. There is

no possible doubt about the intelligence, the curiosity, and the mental agility

of a few of the old Greeks. Neither can there be any doubt about the greatness

of their influence on subsequent European culture, even though for the last

five hundred years the world has been in active revolt against Greek ideas and

ideals. For a very long time we have been taught that

after the Greeks there came long periods in which men were not so intelligent

as the Greeks had been, and that it was not until the Renaissance that the so

intelligent Greek point of view was to some extent recovered. I

believe that this teaching, like its general acceptance, has come about because

people have confused their ideas of what constitutes intelligence with their

ideas about what they have thought of, in the Arnoldian

sense, as culture, Culture and intelligence are quite different things.

In actual life, people who exemplify Arnoldian culture are no more intelligent

than other people, and they have very rarely been among the great creators,

the discoverers of new ideas, or the leaders towards social enlightenment. Most

of what we think of as culture is little more than the unquestioning acceptance

of standardized values.

Historians until very recent times have been literary men and philologues. As

students of the past they have rarely found anything they were not looking for.

They have been so full of wonder at what the Greeks

said, that they have paid little attention to what the Greeks did not do or

know. They have been so full of horror at what the Dark Ages did

not say that they have paid no attention to what they

did do and know. Modern research, by men who are aware of low subjects

like economics and technology, is changing our ideas about these matters. In

the Dark Ages, to use their traditional name, there was little assured leisure

for pursuit of the niceties of literature, art, philosophy, and theoretical

science, but many people, nevertheless, addressed their perfectly good minds

to social, agricultural, and mechanical problems. Moreover, all through those

academically debased centuries, so far from there having been any falling off

in mechanical ability, there was an unbroken series of discoveries and inventions

that gave the Dark Ages, and after them the Middle Ages, a technology, and,

therefore, a logic, that in many most important respects far surpassed anything

that had been known to the Greeks or to the Romans of the Western Empire.

As to the notorious degradation of the Dark Ages, it is to be remembered that

during them Byzantium was an integral part of Europe and actually its great

political centre of gravity. There was no iron curtain between the East and

the West. Intercourse between them was constant and unbroken, and for long periods

Byzantium was in actual control of large parts of Italy. We forget the meaning

of the word Romagna, and of the Byzantine arts of Venice and South Italy. These

things should be borne in mind in view of the silent implication that Byzantium,

from which later on so much of Greek learning came to the West, never lost that

learning. This implication is probably quite an untrue one. Both

East and West saw a great decline in letters. The Academy at Athens was closed

in A.D. 529. At Byzantium the university was abolished in the first half of

the eighth century. Psellos said that in the reign of the Emperor

Romanos (1028-34) the learned at Constantinople had not reached further than

the portals of Aristotle and only knew by rote a few catch words of Platonism.

The Emperor Constantine (1042-54) revived the university on a small scale and

made Psellos its first professor of philosophy. Psellos taught Platonism, which

he personally preferred to the then reigning variety of Aristotelianism. So

far as concerned intellectual activity there was probably much more in the West

than in the East, though directed at such different ends that it evaded the

attention of students trained in the traditional classical lore. Where the East

let so much of the inherited culture as it retained become gradually static

and dull, the West turned from it and addressed its intelligence to new values

and new things.

In spite of all this it was the Dark Ages that transmitted to us practically

all we have of Greek and Roman literature, science, and philosophy. If

the Dark Ages had not to a certain extent bee interested in such things it is

probable that we should have very little of the classical literatures. People

who laboriously copy out by hand the works of Plato and Archimedes Lucretius

and Cicero, Plotinus and Augustine, cannot be accused of being completely devoid

of so-called intellectual interests. We forget that the Greeks themselves had

forgotten much of their mathematics before the Dark Ages began, and it is easy

to overlook such a thinker as Berengar, in the West, who, about the middle of

the eleventh century, challenged much of what we regard as Greek thought by

asserting that there is no substance in matter aside from the accidents.

The intelligence, as distinct from the culture, of the Dark and Middle Ages,

is shown by the fact that in addition to forging the political foundations of

modern Europe and giving it a new faith and morality, those Ages developed a

great many of what today are among the most basic processes and devices. The

Greeks and Romans had no thought of labour-saving devices and valued machinery

principally for its use in war-just as was the case in the Old South of the

United States, and for much the same reasons. To see this, all one has to do

is to read the tenth book of Vitruvius. The Dark and Middle Ages in their poverty

and necessity produced the first great crop of Yankee ingenuity.

The breakdown of the Western Empire and the breakdown of its power plant were

intimately related to each other. The Romans not only inherited all the Greek

technology but added to it, and they passed all this technology on to the Dark

Ages. It consisted principally in the manual dexterity

and the brute animal force of human beings, most of them in bondage.

In the objects that have come down to us from classical times there is little

evidence of any actively working and spreading mechanical ingenuity. As shown

by Stonehenge, the moving and placement of heavy stones goes back of the beginnings

of written history. The Romans did not, however, pass on to the Dark Ages in

the West the constantly renewed supply of slaves that constituted the power

plant about which the predatory Empire was built. In

other words, the Dark Ages found themselves stranded with no power plant and

with no tradition or culture of mechanical ingenuity that might provide another

power plant of another kind. They had to start from scratch. The

real wonder, under all the circumstances, is not that they did so badly but

that they did so well.

The great task of the Dark and the Middle Ages was to build for a culture of

techniques and technologies. We are apt to forget that

it takes much longer to do this than it does to build up a culture of art and

philosophy, one reason for this being that the creation of a culture of technologies

requires much harder and more accurate thinking. Emotion plays a

surprisingly small part in the design and operation of machines and processes,

and, curiously, you cannot make a machine work by flogging

it. When the Middle Ages had finally produced the roller press, the

platen press, and the type-casting mould, they had created the basic tools for

modern times.

We have for so long been told about the philosophy,

art, and literature, of classical antiquity, and have put them on such a pedestal

for worship, that we have failed to observe the patent fact that philosophy,

art, and literature can flourish in what are technologically very primitive

societies, and that the classical peoples were actually iii many ways of the

greatest importance not only very ignorant but very unprogressive.

Progress and improvement were not classical ideals. The trend of classical thought

was to the effect that the past was better than the present and that the story

of human existence was one of constant degradation. In spite of all the romantic

talk about the joy and serenity of the Greek point of view, Greek thought actually

developed into a deeply dyed pessimism that coloured and hampered all classical

activities.

It is, therefore, worth while to give a short list of some of the things the

Greeks and Romans did not know, and that the Middle Ages did know. For most

of the examples I shall cite I am indebted to Lynn White's remarkable essay

on Technology and Invention in the Middle Ages. (Speculum, vol XV, p.

141 (April 1940).

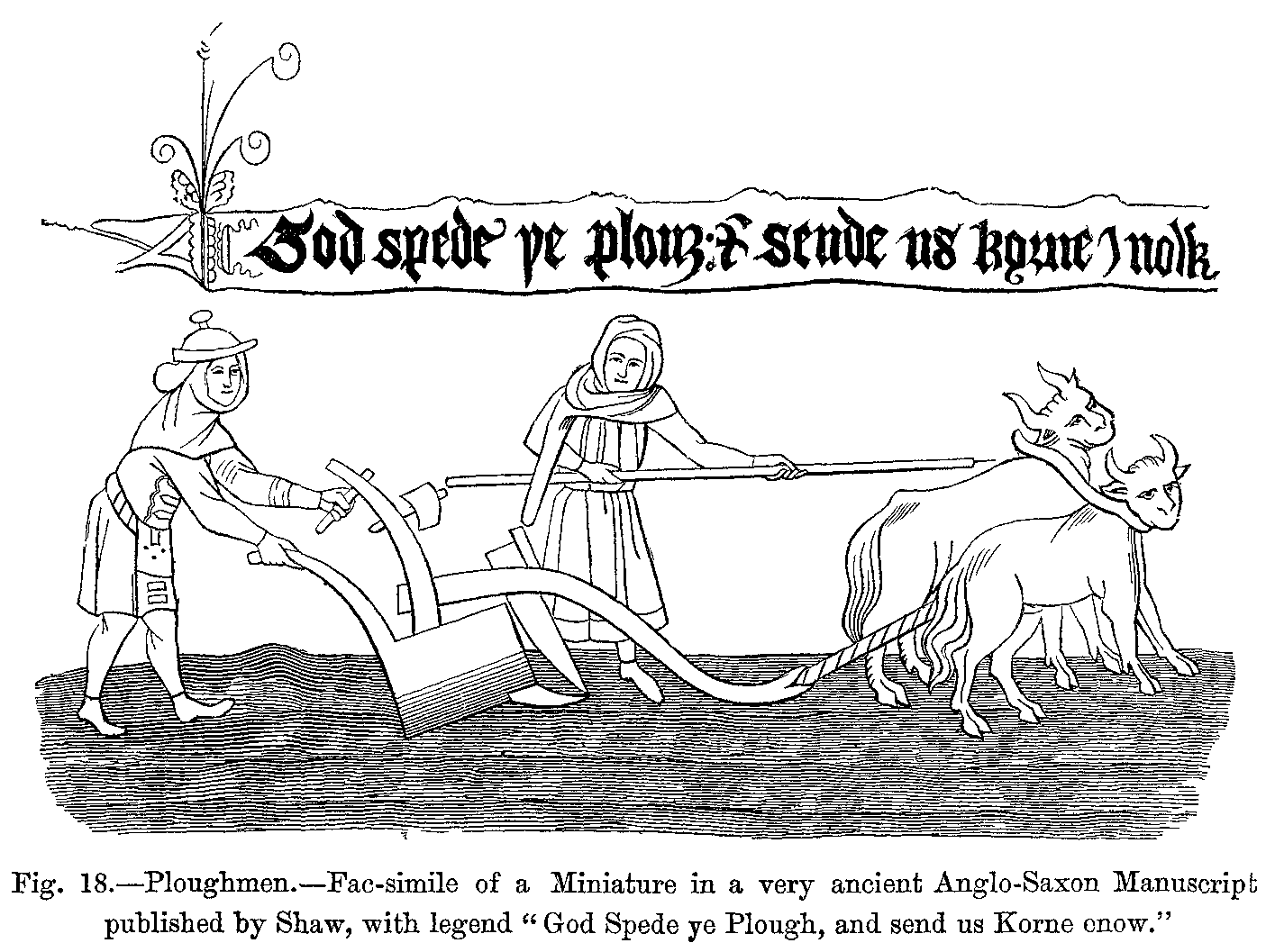

The classical Greeks and Romans, although horsemen,

had no stirrups. Neither did they think

to shoe the hooves of their animals with plates of metal nailed to them. Until

the ninth or tenth centuries of our era horses were so harnessed that they pushed

against straps that ran high about their necks in such a way that if they threw

their weight and strength into their work

they strangled themselves. Neither did the classical peoples know how to

harness draft animals in front of each other so that large teams could be used

to pull great weights. Men were the only animals the ancients had that could

pull efficiently. They did not even have wheelbarrows....They made little or

no use of rotary motion and had no cranks by which to turn rotary and reciprocating

motion into each other. They had no windmills. Such water wheels as they had

came late and far between. The classical Greeks and Romans, unlike the Middle

Ages, had no horse collars, no spectacles, no

algebra, no gunpowder, no compass, no cast iron, no paper, no deep plows,

no spinning wheels, no methods of distillation, no

place value number systems-think of trying to extract a square root with

either the Greek or the Roman system of numerals!

The engineers who, in the

sixth century A.D., brought the great monolith that caps the tomb of Theodoric

across the Adriatic and set it in place were in no way inferior to the Greek

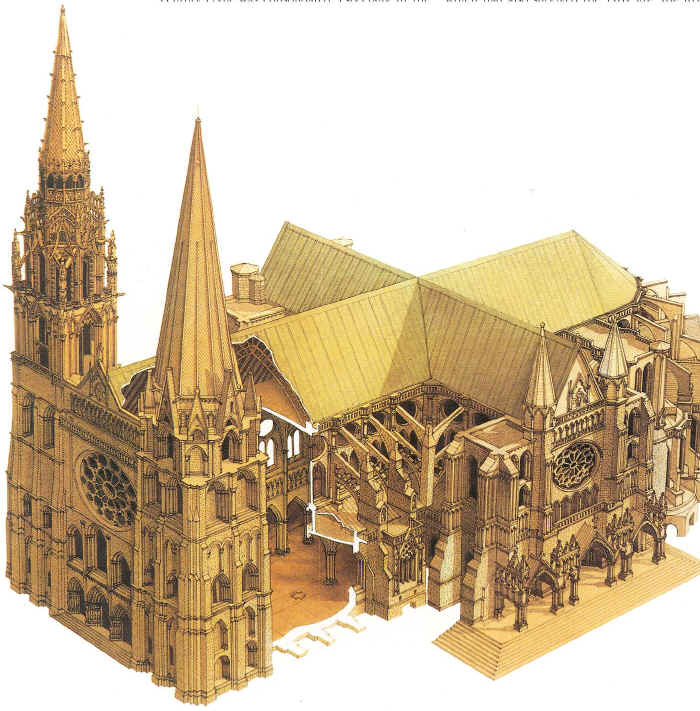

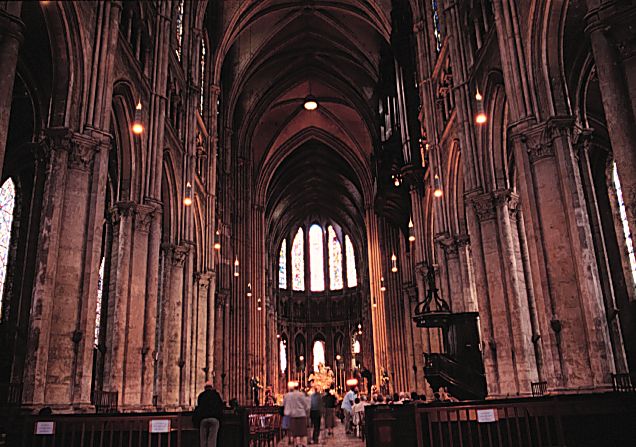

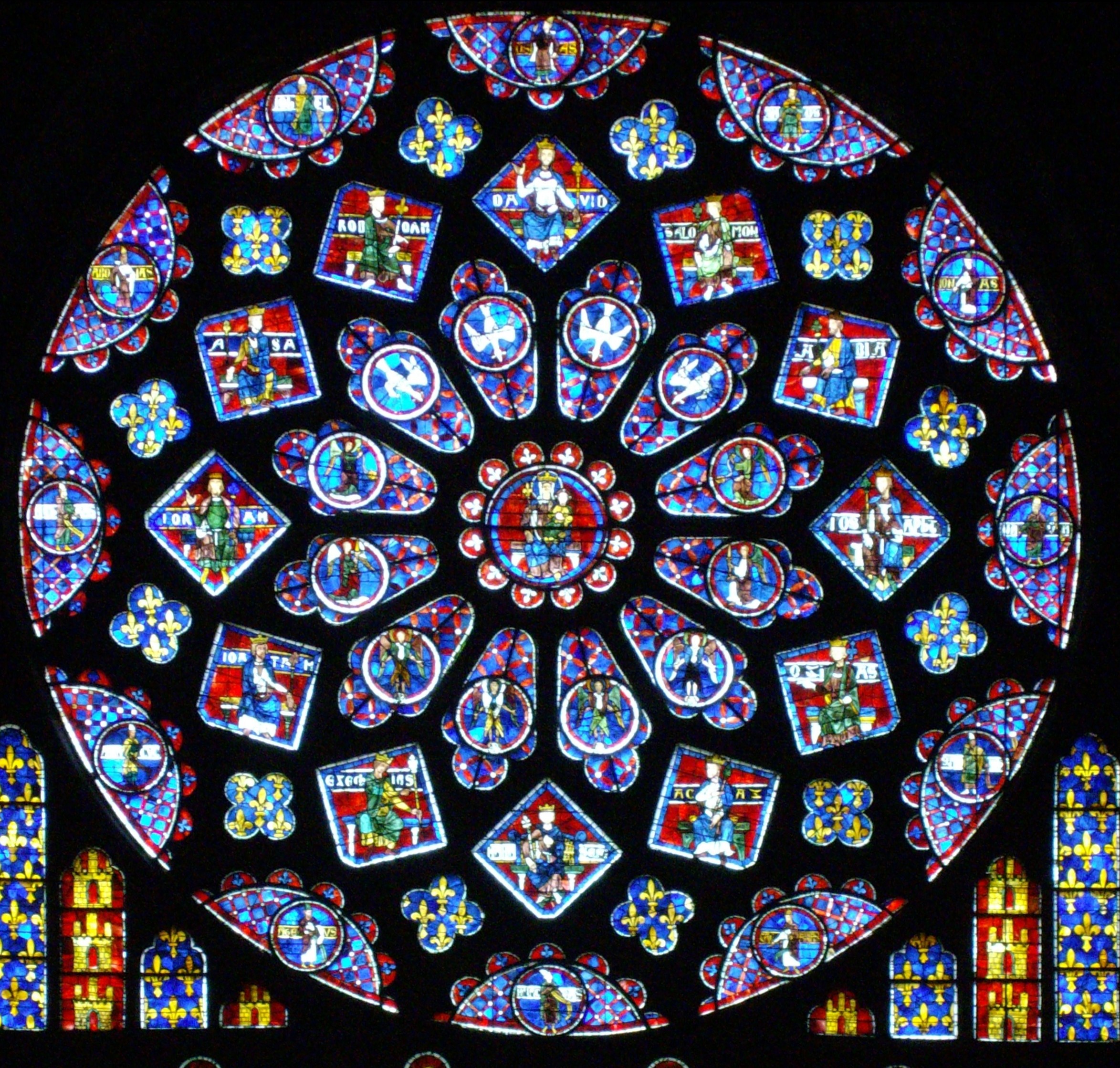

and Roman engineers. The twelfth century cathedrals

of France represent a knowledge of engineering, of stresses and strains, and

a mechanical ingenuity far beyond anything dreamed of in classical times. The

Athenian Parthenon, no

matter what its aesthetic qualities, was but child's play as engineering compared

to buildings like the cathedrals at Rheims and Amiens.

It is perhaps hard for us, who have been educated in the fag end of the traditional

humanistic worship of the classical peoples, to realize that what happened in

the ninth and tenth centuries of our era in North-Western Europe was an economic

revolution based on animal power and mechanical ingenuity which may be likened

to that based on steam power which took place in the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries. It shifted the economic and political centre of gravity

away from the Mediterranean with its technological ineptitude to the north-west,

where it has been ever since. This shift may be said to have had its first official

recognition in the two captures of Constantinople in 1203 and 1204. It is customary

from the philological point of view to regard these captures as a horrible catastrophe

to light and learning, but in fact they actually led

to the wiping out of the most influential centre of unprogressive backward-looking

traditionalism there was in Europe.

In view of the things the Greeks and Romans did not know, it is possible that

the real reason for the so-called darkness of the Dark Ages was the simple fact

that they were still in so many ways so very classical.

It is well to remember things of this kind when we are told about the charm

of life in Periclean Athens or in the Rome of the Antonines, and how superior

it was to that of all the ages that have succeeded them. The inescapable facts

are that the Greek and Roman civilizations were based on slavery of the most

degrading kind, that slaves did not reproduce themselves, that the supply was

only maintained by capture in predatory warfare, and that slavery is incompatible

with the creation of a highly developed technology.

Although a few of the highly educated Greeks went in for pure mathematics and

theoretical science neither they nor the educated Romans ever lowered themselves

to banausic pursuits. They never thought of doing laborious,

mechanical things more efficiently or with less human pain and anguish-unless

they were captured and sold into slavery, and what they thought then did not

matter. As all these things in the end are of great ethical importance,

it should also be remembered that the so cultured Greeks left it to the brutal

Romans to discover the idea of humanity, and that it

was not until the second century of our era that the idea of personality was

first given expression. If the educated

Greeks and Romans had demeaned themselves by going in for civil technology as

hard as they did for a number of other things the story might have been different.

But they did not, even in matters that would have been greatly to the advantage

of the governing groups in society.

Thus, the Romans are famous for the military roads they built all over the Empire,

and the Dark and Middle Ages are held up to scorn for having let those roads

go to pieces. However, if we think that those roads were not constructed for

civil traffic but as part of the machinery of ruthless military domination of

subject peoples, it is possible to regard their neglect as a betterment. Those

later Ages substituted other kinds of roads for the Roman variety, roads that

were not paved with cemented slabs of stone for the quicker movement of the

slogging legions, but roads that, if paved at all, were paved with cobbles,

which in many ways and from many unmilitary points of view were more efficient

It is significant that the world has never gone back to the Roman methods of

road building, and that as late as the days of my own youth streets in both

London and New York were still paved with cobbles.

To take another example: the Greeks were great seamen. The Athenian Empire was

a maritime empire. But the Greeks rowed and did not

sail. If you cannot beat up into the wind you cannot sail. All the

Greeks' sails enabled them to do was to blow down the wind a little faster.

They did not dare to venture beyond sight of land. The rudder at the end of

the keel and the lateen and fore and aft sails, like the mariner's compass,

were acquisitions of the Dark and Middle Ages. Actually, until the Renaissance

and even later, the Mediterranean peoples never learned how to do what we call

sailing. The Battle of Lepanto, in 1571, was fought by men in rowboats-large

row-boats, to be sure-which grappled with each other so that their men could

fight it out hand to hand. The test as between the thought based on the ancient

row-boat techniques and that based on the mediaeval deep-water sailing came

seventeen years after Lepanto, when the great Spanish Armada met the little

English fleet. This was the crucial battle in the last long-drawn-out attempt

of the Mediterranean to recover the hegemony it had lost before the end of the

tenth century and in it went down to utter and disastrous defeat. Within a little

more than a hundred years it was distant England that held Gibraltar and Port

Mahon and was the great Mediterranean sea power.

On the intellectual and

administrative side of ancient life we meet the same lack of mechanical ingenuity.

Few people have been more given to books and reading than the upper classes

of Greece and Rome. Books were made by copying by hand. The trade in them flourished

at Athens, at Alexandria, and at Rome. Great libraries were formed in the Hellenistic

period and in the early centuries of the Roman Empire. Plato says that in his

time a copy of Anaxagoras could be bought for a drachma, which, according to

the Oxford Dictionary, may be considered as being worth less than twenty-.five

cents. Pliny, the Younger, in the second century of our era, refers to an edition

of a thousand copies of a text. Had the Romans had any mechanical way of multiplying

the texts of their laws and their legal and administrative rulings and all the

forms needed for taxation and other such things, an infinite amount of time

and expense would have been saved. But I cannot recall that I have either read

or heard of any attempt by an ancient to produce a book or legal form by mechanical

means.

In its way the failure of the ancients to address their

minds to problems of the kinds I have indicated is one of the most cogent criticisms

that can be made of the kind of thought in which they excelled and of its great

limitations. The Greeks were full of all sorts of ideas about all

sorts of things, but they rarely checked their thought by experiment and they

exhibited little interest in discovering and inventing ways to do things that

had been unknown to their ancestors. They refined on ancient processes, and

in the Hellenistic period they invented ingenious mechanical toys, but it is

difficult to point to any technological or labour-saving devices invented by

them that were of any momentous social or economic importance. This is shown

in several odd ways. For one, the learned writers of

accounts of daily life in ancient times have no hesitancy in mixing up details

taken from sources that are generations apart, as though they all related to

one unchanging state of affairs. For another, modern students have

not hesitated to play up as a great and profound virtue the lack of initiative

of the Greek craftsmen in looking for new subjects and new manners of work.

Thus Percy Gardner, lauding the Greek architects and stone-cutters, in his article

on Greek Art in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, says,

'Instead of trying to invent new schemes, the mason contents himself with improving

the regular patterns until they approach perfection.' One can hear the unction

drip from that deadly word 'perfection'-one of the greatest inhibitors of intelligent

thought that is known to man. The one epoch-making discovery in architectural

construction that was made by the classical peoples seems to have been the arch-but

the Romans had to bring it with them to Byzantium. Apparently there were no

Greek voussoirs, i.e. stones so cut and shaped as to fit together in an arch

or vault.

Learned men have devoted many large and expensive volumes to the gathering together

of all the literary evidence there is about classical painting and drawing and

to the reproduction of all the specimens of such drawing and painting as have

been found. It appears from these books that there are no surviving classical

pictorial statements, except such as were made incidentally in the decoration

of objects and wall surfaces. For such purposes as those there was no need or

call for methods to exactly repeat pictorial statements. From the point of view

of art as expression or decoration there is no such need, but from that of general

knowledge, science, and technology, there is a vast need for them. The lack

of some way of producing such statements was no less than a road block in the

way of technological and scientific thought and accomplishment.

Lest it be thought that in saying this I am merely expressing a personal prejudice,

I shall call your attention to what was said about it by a very great and unusually

intelligent Roman gentleman, whose writings are held in particularly high esteem

by all students of classical times. Some passages in the Natural History of

Pliny the Elder, a book that was written in the first century of our era, tell

the story in the most explicit and circumstantial of manners. As pointed out

by Pliny, the Greeks were actually aware of the road block from which they suffered,

but far from doing anything about it they accommodated

themselves to it by falling back into what can only be called a known and accepted

incompetence. More

than that, I believe, they built a good deal of their philosophy' about this

incompetence of theirs. In any case, what happened affords a very apposite example

of how life works under the double burden of a pessimistic philosophy and a

slave economy. There is nothing more basically optimistic than a new and unprecedented

contrivance, even though it be a lethal weapon.

Pliny's testimony is peculiarly valuable because he was an intelligent eye-witness

about a condition for which, unfortunately, all the physical evidence has vanished.

He cannot have been the only man of his time to be aware of the situation and

the call that it made for ingenuity. Seemingly his statement has received but

slight attention from the students of the past. This is probably due to the

fact that those students had their lines of interest laid down for them before

the economic revolution that camee to England in the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries and did not reach Germany until after 1870, at a time when

the learned and the gentry knew nothing and cared less about what they regarded

as merely mechanical things. The preoccupation of the

post-mediaeval schools and universities with classical thought and literature

was probably the greatest of all the handicaps to technological and therefore

to social advance. It would be interesting to see a chronological

list of the establishments of the first professorships of engineering. With

rare exceptions the mechanical callings and knowledges were in the past as completely

foreign to the thought and life of the students of ancient times as they were

to the young elegants who attended the Academy or walked and talked with Aristotle.

So far as I have been able to observe they still are.

In any event, according to Bohn, what Pliny said was this: 'In addition to these

(Latin writers), there are some Greek writers who have treated of this subject

(i.e. botany)... Among these, Crateuas, Dionysius, and Metrodorus, adopted a

very attractive method of description, though one which has done little more

than prove the remarkable difficulties which attended it. It was their plan

to delineate the various plants in colours, and then to add in writing a description

of the properties which they possessed. Pictures, however, are very apt to mislead,

and more particularly where such a number of tints is required for the initiation

of nature with any success; in addition to which, the diversity of copyists

from the original paintings, and their comparative degrees of skill, add very

considerably to the chances of losing the necessary degree of resemblance to

the originals...' (Chap. 4, Book 25).

'Hence it is that other writers have confined themselves to a verbal description

of the plants; indeed some of them have not so much as described them even,

but have contented themselves for the most part with a bare recital of their

names, considering it sufficient if they pointed out their virtues and properties

to such as might feel inclined to make further inquiries into the subject'

(Chap 5, Book 25 - Quoted by permission of G. Bell & Sons, Ltd., the present

publishers of Bohn's Library).

The plant known as "paeonia"

is the most ancient of them all. It still retains the name of him who was the

first to discover it, being known also as the "pentorobus" by some,

and the "glyciside" by others; indeed this is one of the great difficulties

attendant on forming an accurate knowledge of plants, that the same object had

different names in different districts' (Chap. 10, Book 25). '

It is to be noted that in his account of the breakdown of Greek botany, Pliny

does not fall back upon general ideas of a woolly kind. There is no 'Zeitgeist'

explanation, no historicism, no suggestion that things were not done simply

because people in their wisdom and good taste preferred not to do them even

though of course they could have done them if they had wanted to. Pliny's reason

is as hard and brutal a fact as a bridge that has collapsed while being built.

This essay amounts to little more than a summary account of the long slow discovery

of ways to erect that bridge.

In view of this I shall rephrase what Pliny said: The Greek botanists realized

the necessity of visual statements to give their verbal statements intelligibility.

They tried to use pictures for the purpose, but their only ways of making pictures

were such that they were utterly unable to repeat their visual statements wholly

and exactly. The result was such a distortion at the hands of the successive

copyists that the copies became not a help but an obstacle to the clarification

and the making precise of their verbal descriptions. And so the Greek botanists

gave up trying to use illustrations in their treatises and tried to get along

as best they could with words. But, with words alone, they were unable to describe

their plants in such a way that they could be recognized- for the same things

bore different names in different places and the same names meant different

things in different places. So, finally, the Greek botanists gave up even trying

to describe their plants in words, and contented themselves by giving all the

names they knew for each plant and then told what human ailments it was good

for. In other words, there was a complete breakdown of scientific description

and analysis once it was confined to words without demonstrative pictures.

What was true of botany as a science of classification

and recognition of plants was also true of an infinite number of other subjects

of the very greatest importance and interest to men. Common nouns

and adjectives, which are the materials with which a verbal description is made,

are after all only the names of vaguely described classes of things of the most

indefinite kind and without precise concrete meanings, unless they can be exemplified

by pointing to actual specimens. In the absence of actual specimens the best

way (perhaps the only way) of pointing is by exhibiting properly made pictures.

We can get some idea of this by trying to think what a descriptive botany or

anatomy, or a book on machines or on knots and rigging, or even a sempstress's

handbook, would be like in the absence of dependable illustrations. The only

knowledge in which the Greeks made great advances were geometry and astronomy,

for the first of which words amply suffice, and for the second of which every

clear night provides the necessary invariant image to all the world.

Ali kinds of reasons have been alleged in explanation of the slow progress of

science and technology in ancient times and in the ages that succeeded them,

but no reference is ever made to the deterrent effect of the lack of any way

of precisely and accurately repeating pictorial statements about things observed

and about tools and their uses. The revolutionary techniques that filled this

lack first came into general use in the fifteenth century. Although we can take

it for granted that the making of printed pictures began some time about 1400,

recognition of the social, economic, and scientific, importance of the exact

repetition of pictorial statements did not come about until long after printed

pictures were in common use. This is shown by the lateness of most of the technical

illustrated accounts of the techniques of making things. As examples I may cite

the first accounts of the mechanical methods of making exactly repeatable statements

themselves. Thus the first competent description of the tools and technique

of etching and engraving was the little book that Abraham Bosse published in

1645; the first technical account of the tools and processes used in making

types and printing from them was that published by Joseph Moxon in 1683; and

the first similar account of woodcutting, the oldest of all these techniques,

was the Traité of J. M. Papillon, which bears on its title page the date

1766. It is not impossible that Moxon's Mechanick Exercises, which were published

serially in the last years of the seventeenth century, had much to do with England's

early start in the industrial revolution.

Anyone who is gifted with the least mechanical ingenuity can understand these

books and go and do likewise. But he can do so only because they are filled

with pictures of the special tools used and of the methods of using them. Parts

of Moxon's account of printing can be regarded as studies in the economy of

motion in manipulation. I have not run the matter down, butI should not be surprised

if his book were not almost the first in which such things were discussed.

Of many of the technologies and crafts requiring particular manual skills and

the use of specialized tools there seem to have been no adequate accounts until

the completion of the great and well illustrated Encyclopaedia of Diderot and

his fellows in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, just before the

outbreak of the French Revolution. But the Encyclopaedia was a very expensive

and very large set of volumes, intended for and limited to the use of the rich.

Curiously, the importance of its contribution to a knowledge of the arts and

crafts has attracted comparatively little attention as compared to that which

has been given to its articles on political matters, although there is good

reason to think that they had equally great results.

The last century is still so close to us and we are so busy keeping up with

the present one, that it is hard for us to realize the meaning of the fact that

the last hundred and fifty years have seen the greatest and most thorough going

revolution in technology and science that has ever taken place in so short a

time. In western Europe and in America the social, as well as the mechanical,

structure of society and life has been completely refashioned. The late Professor

Whitehead made the remarkable observation that the greatest invention of the

nineteenth century was that of the technique of making inventions. But he did

not point out that this remarkable invention was based in very large measure

on that century's sudden realization that techniques and technologies can only

be effectively described by written or printed words when they are accompanied

by adequate demonstrative pictures.

The typical eighteenth-century methods of book illustration were engraving and

etching. Etchings and engravings have always been expensive to make and to use

as book illustrations. The books that were fully illustrated with them were,

with few exceptions, intended for the consumption of the rich and the traditionally

educated classes. In the eighteenth century the title pages of these books sometimes

described them as being 'adorned with elegant sculptures', or other similar

words. The words 'adorned' and 'elegant' tell the story of their limitations,

mental and financial alike. Lest it be thought that the prase I have just quoted

came from some polite book of verse or essays, I may say that it has stuck in

my memory ever since at the age of ten I saw it on the title page of a terrifying

early eighteenth-century edition of Foxe's Martyrs, in which the illustrators

went all out to show just what happened to the Maryian heretics. Under the circumstances

I can think of few phrases that throw more light on certain aspects of eighteenth-century

life and thought.

Although hundreds of thousands of legible impressions could be printed at low

cost from the old knife-made woodcuts, the technique of woodcutting was not

only out of fashion in the eighteenth century, but its lines were too coarse

and the available paper was too rough for the woodcut to convey more than slight

information of detail and none of texture.

At the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century

a number of very remarkable inventions were made. I shall mention but three

of them. First, Bewick,

in the 1780's, developed the technique of using an engravers, tool on the end

of the wood, so that it became possible to produce from a wood-block very fine

lines and delicately gradated tints, provided it were printed on smooth and

not too hard paper. Next, in 1798,

Robert, in France, invented, and shortly afterwards, in England, Fourdrinier

perfected, a paper-making machine, operated by power, either water or

steam, which produced paper by a continuous process. It also made possible the

production of paper with a wove surface that was smoother than any that had

previously been made in Europe. When fitted with calendar roils the machine

produced paper that was so smooth it was shiny. Finally, just before 1815,

Koenig, a German resident in England, devised for the (London) Times

a printing press that was operated by power and not by the strength of men's

backs. In connection with a revival of Ged's earlier invention of stereotyping,

these inventions brought about a very complete revolution in the practice of

printing and publishing. The historians of printing have devoted their attention

to the making of fine and expensive books, and in so doing they have overlooked

the great function of books as conveyors of information. The history of the

cheap illustrated book and its role in the self-education of the multitude has

yet to be written.

It took but a comparatively short time for these three or four inventions to

spread through the world. As they became familiar there was such a flood of

cheap illustrated informative books as had never before been known. Nothing

even approaching it had been seen since the sixteenth century. It took only

a few decades for the publishers everywhere to begin turning out books of this

kind at very low prices. In a short time the world ceased to talk about the

'art and mystery' of its crafts. In France they said that the Revolutionary

law abolishing the guilds opened the careers to the talents, but it was actually

these heap illustrated informative books that opened the crafts to everyone,

no matter how poor or unlearned, provided only that he knew how to read and

to understand simple pictures. As examples of this I may cite the well-known

Manuels Roret, the publication of which goes back to 1825, and the English Penny

Cyclopaedia which began in 1833. It is to be noted that for a long time in the

nineteenth century the upper classes and the traditionally educated made few

contributions to the rapidly lengthening list of new inventions, and that so

many of those inventions were made by what in England until very recent years

were condescendingly referred to as 'self-educated men'. The fact was that the

classicizing education of the men who were not self educated prevented them

from making inventions.

In the Renaissance they had found a solution of the dilemma of the Greek botanists

as described by Pliny. In the nineteenth century informative books usefully

illustrated with accurately repeatable pictorial statements became available

to the mass of mankind in western Europe and in America. The result was the

greatest revolution in practical thought and accomplishment that has ever been

known. This revolution was a matter as momentous from the ethical and political

points of view as from the mechanical and economic ones. The masses had begun

to get the one great tool they most needed to enable them to solve their own

problems. Today the news counters in our smallest towns are piled with cheap

illustrated magazines at which the self-consciously educated turn up their noses,

but in those piles are prominently displayed long series of magazines devoted

to mechanical problems and ways of doing things, and it would be well for the

cultured if they but thought a little about the meaning of that.

I think it can be truthfully said that in 1800 no man anywhere, no matter how

rich or highly placed, lived in such physical comfort or so healthily, or enjoyed

such freedom of mind and body, as do the mechanics of today in my little Connecticut

town.

If any one thing can be credited with this it is the pervasion of the cheap

usefully informative illustrated book

Prints

and visual communications, The Road Block Broken - Tkhe Fifteenth

Century pags 21 - 22 William

M.lvins Jr:

Prints began to pervade

the life and thought of Western Europe in the fifteenth century. It is therefore

necessary to take a glance at what we have been told about that century.

Probably the worst way there is to discover the most

important thing done in any history period is to take the word of that period

for it. What to the generation of its occurrence is merely a casual

happening, an amusing toy, or an impractical intellectual or physical adventure,

in time frequently becomes all-important for the world.

In spite of this we are still asked to think of the

Renaissance in terms of what some literary people of that time thought were

the most important things it did. Thus almost every book dealing

with the Renaissance says that the principal events of the fifteenth century

were the recoveries of Greek thought and of the classical forms of art. This

statement is so customary and is made with such an air of finality that most

of us have come to believe it. And, yet, on the very face of the

record, it is impossible to believe it. We have forgotten that the literary

and artistic men who evolved and told us this fairy tale were much more ignorant

of the Middle Ages, and even of the Renaissance itself, than the Middle Ages

were ignorant of Greek thought.

In the first place, what is called Greek thought is not a homogeneous body of

doctrine and knowledge reflecting a reasoned and unified attitude towards life

and the world what remains of it is a highly accidental heap of notions and

odds and ends of the most violently contradictory kinds. If you care to look

for it you can find a phrase in it that can be twisted to the purpose of almost

anything you want to argue on any side of any problem. The

Greeks never agreed about anything, they actually knew very little, it was quite

customary for them to be intellectually dishonest, their arguments were designed,

not to bring out the truth, but to down the other fellow in a forensic victory,

and they had very loose and careless tongues. Although we are always

told that Aristotle discovered logic, it should be obvious that no one man could

possibly have been its discoverer. Much of Aristotle's teaching was very illogical,

and on the whole it undoubtedly hampered subsequent thought much more than it

helped it.

In the second place, it is easy to forget that many of the scholastic doctrines

and modes of thought which had dominated much of mediaeval thinking were specifically

Aristotelian, which is to say that they were Greek. The shift away from scholasticism

was not so much the result of any discovery of Greek thought as a revulsion

from it. That this shift took the initial form of a limited and superficial

fashion for neo-Platonism and for the exterior nudity, though not for the interior

content, of Roman art, can be regarded as little more than a passing phase of

the basic revolt.

However important it may have seemed to certain restricted and loquacious portions

of Renaissance society, this fashion in itself made singularly little difference

to the part of the world that was beginning to think new thoughts and to do

new things.

Contrary to what we have long been taught, the effective

thinking of the Renaissance was not merely a resurrection of classical ideas.

As we can see it today, the really great event of the Renaissance was the emergence

of attitudes, and kinds and objects of thought that were neither Aristotelian

nor Platonic, nor yet Greek at all, but in so far as they had never attracted

the attention of the writers and literary men, quite new and different. To a

great extent they were the results of materials and technological problems completely

unknown to the ancient world. What actually happened in the fifteenth century

was the effective beginning of that practical struggle for liberation from the

trammels of Greek ideas which has been the outstanding characteristic of the

last five hundred years.

Child's play as engineering compared to buildings like the cathedrals at Rheims and Amiens.