From where to start?

This is interwoven with about us and Proposition

Best bet, go to his biography and then browse his quotes, maybe starting from sundry topics...

What resources use?

Once upon a time there were only printed books, magazines, newspapers, journals and the like. Suddenly, maybe not so suddenly, there are Internet, websites, computers, Ipad's and the like. And then there is the ownership about the subject and what it is officially all about...

Just to balance it out and as an argument, according to the Modern Language Association International Bibliography, as of 2014, Ulysses has generated 2,656 scholarly studies. By contrast, the MLA lists only 1,477 entries for Marcel Proust's masterwork, In Search of Lost Time, and only 414 entries for Mrs. Dalloway, whose author, Virginia Woolf dismissed Ulysses as "a mis-fire." In a diary entry for September 6, 1922, she wrote: "The book is diffuse. It is brackish. It is pretentious. It is underbred, not only in the obvious but in the literary sense."

This paradox is discussed elsewhere. The sequence and history of his works editions also. The cornucopia of studies, information, papers, websites, etc., also.

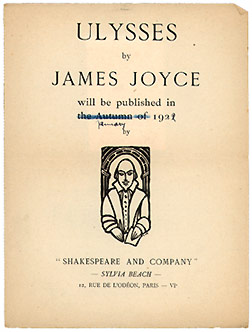

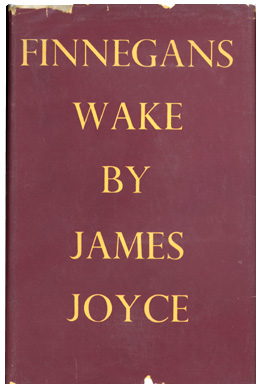

The intention of this project is to create an axiom for deciphering the gibberish and gobbledygook that after all became the style of James Joyce at Finnegan's Wake and by extension, provide an affordable way to understand and figure out Joyce`s mental process applying it to his works. Since this whole job is a Work in Progress, and probably will remain so, the idea is to link all works of Joyce, which comprises three novels (A Portrait of the Artist as Young Man, Ulysses and Finnegan's Wake), plus the short story collection Dubliners. If it is possible to say so, if this job is a theorem, the proposition is to demonstrate by analogy that James Joyce style is just but noise in a communication process, printed books, which bring in their inception severe limitations that are extensively used by Joyce. It is also taken for grant that It is non existing at the Short Stories, he sets himself up to that in the Portrait, matures it in Ulysses and fully blossoms at Finnegan's.

Incidentally, Ulysses is the real beginning of James Joyce and his most praised work and although maybe it would make more sense to create the above axiom or theorem for Ulysses, I would dare to say that the same way Joyce claimed that if Dublin were to be destroyed by some catastrophe, it could be rebuilt brick by brick, using his novel Ulysses, James Joyce himself, if all his other works were destroyed, could be figured out by Finnegan's Wake.

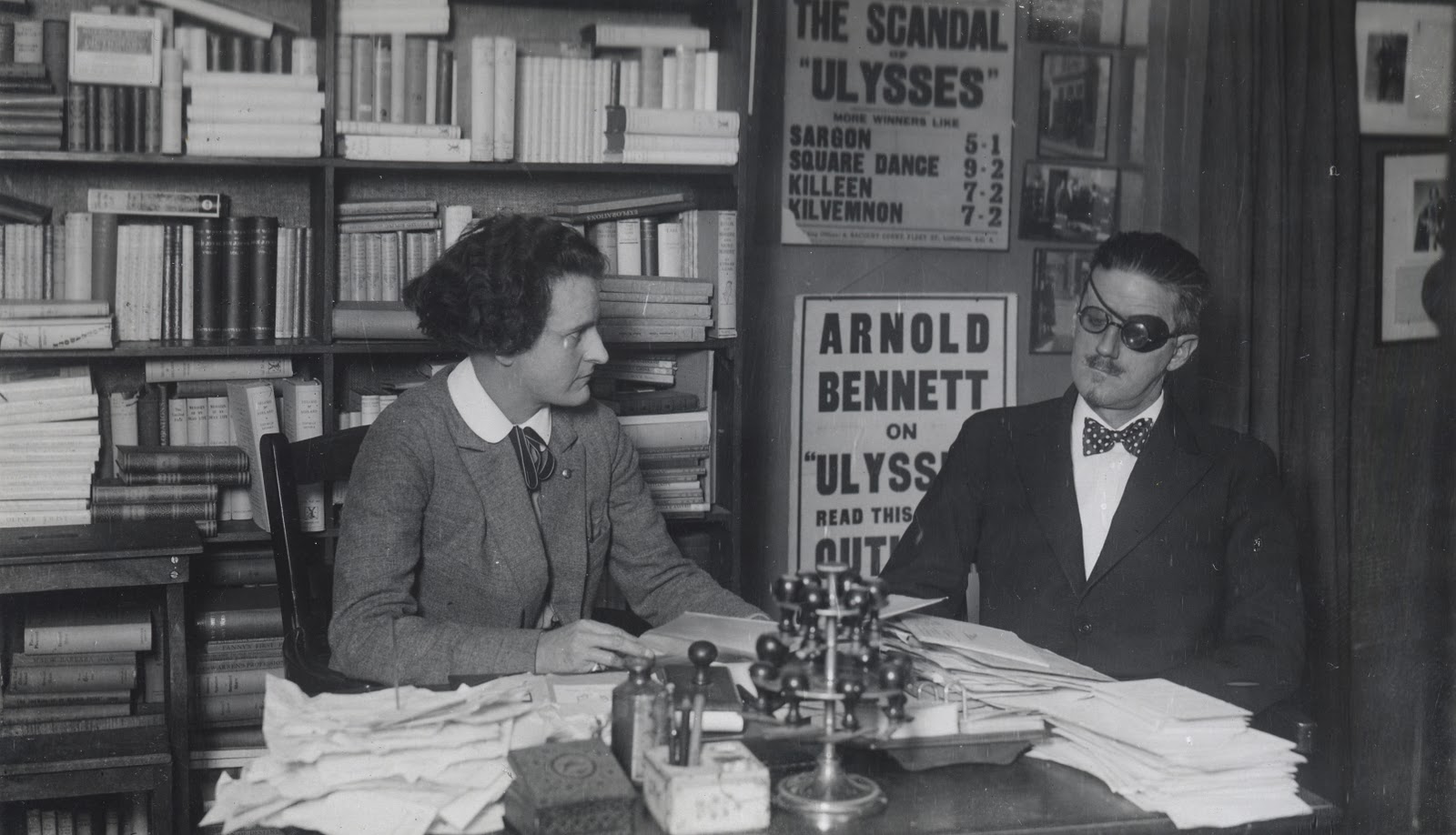

The reason why it was chosen this picture of James Joyce and Sylvia Beach as the entry point for this job is that and also explained elsewhere.

Whatever James Joyce had in mind, did he achieve his purpose? Which were or are the effects of the way he choose to do it on his purpose? Did he indeed transferred to the reader what was on his mind? What he had on his mind? Is it describable on a written text so an average person can figure it out? Did he manage to communicate himself out?

Obviously the discussions above about the paradox of being great and lame, the obstacles to be published and the reception of the then established intelligentsia indicates a resounding NO! And although he is generally accepted as the most influential writer and the biggest one of the 20th century, he is also one of the least read...

It is my belief that the analogies contained here can answer these questions and help to create a frame of understanding on his works. It should be considered an addition to Literature and by no means it is a contender or a replacement to it.

A most appropriate perspective on that is brought out by Dr.Julie Sloan Brannon, in her Who Reads Ulysses?: The Common Reader and the Rhetoric of the Joyce Wars, and I quote:

Chapter one, page 11

JOYCE`S CANONIZATION, in which

PROFESSORS ARE KEPT BUSY

After all, to comprehend Ulysses is not among the recognised learned professions, and nobody should give his entire existence to the job.

"The Joyce Industry": this is the self-applied name for the post-1960 boom in Joyce criticism. The first issue of The James Joyce Quarterly in 1963 inaugurated the arrival of Joyce studies as a full-scale critical field in its own right, and forty years later this journal is still at the center of that field. Simultaneuous with this recognition of Joyce studies as a legitimate filed of inquiry, the biannual International James Joyce Symposia grew from a fairly small gathering of seventy-five scholars in 1967 to a gathering of well over 250 participants from countries spanning the globe at the present time (2003). From the introduction of Ulysses to the wider American literary scene through the famous Woolsey decision of 1933, Joyce went from being a peculiar and obscure Irish writer (often alluded to as obscene but, as in the case of most censored writers, rarely actually read) to a major literary giant in a span of less than ten years, and the center of that activity has been in the United States - a country in which Joyce never set foot.

Ulysses continues to sell upwards of 100 000 copies a year worldwide. Some of these copies, undoubtedly, are sold to students in the university system; but the book is also stocked on the shelves of commercial book-stores like Barnes & Noble, B.Dalton and Waldenbooks. The university then, plays a role in Joyce's reputation, but there are other forces at work, many of which have to do with the publicity machine which thrust Ulysses into the public's eye over eighty years ago. Joyce's reputation rests in part on the academic machinery which created the Joyce industry as we know it, and the process which canonized his works produced a particular kind of Joyce, one which serves the needs of the academic institution which created him. This academic Joyce from the general public's Joyce, a dichotomy I will examine more closely in Chapter Two; but the image of an iconoclastic author whose works are impossible to comprehend without critical intervention finds its roots in the academic Joyce and the critical machinery which supports him. The oft-repeated quote about keeping the professors busy has become a Joycean cliche, and functions in part to imply that Joyce wrote specifically for the professors rather than a broader reading public. The context of the quote, however, is a humorous one which undercuts the surface meaning/ Jacques Benoîs-Mechin, the young an who translated "Penelope" into French for Valery Larbaud's reading in 1921, had begged Joyce for the scheme of the book. Joyce only gave him parts of it and said: "If I gave it all up immediately, I'd lose my immortality. I've put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that's the only way of insuring one's immortality" (Elmann 521). Joyce's view of "the professors" was a wry (although ironically prescient) one. But the effect on this quote, offered ad nauseam and out of context in both scholarly and popular articles as a serious comment on Joyce's intentions, reinforces the academic Joyce who wrote for the professors And for the last fifty years the professors have, indeed been busy.

Long before that, when Joyce died, I quote the following from his obituary in the Nerw York Times of January 13, 1941:

Hailed and Belittled by Critics

The status of James Joyce as a writer never could be determined in his lifetime. In the opinion of some critics, notably Edmund Wilson, he deserved to rank with the great innovators of literature as one whose influence upon other writers of his time was incalculable. On the other hand, there were critics like Max Eastman who gave him a place with Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot among the "Unintelligibles" and there was Professor Irving Babbitt of Harvard who dismissed his most widely read novel, "Ulysses," as one which only could have been written "in an advanced stage of psychic disintegration."

Originally published in 1922, "Ulysses" was not legally available in the United States until eleven years later, when United States Judge John Monro Woolsey handed down his famous decision to the effect that the book was not obscene. Hitherto the book had been smuggled in and sold at high prices by "bookleggers" and a violent critical battle had raged around it.

From these 2656 studies, let's separate the ones used to explain my point, but what I say here is true for all of them, say, the 2656